Frieze Art Week runs the 17th till the 23rd of February this year, meaning many gallery openings, art events, public installations, and fairs happening concurrently all over the city. The bread and butter of this week, though, are the art fairs, and one of the most notable of the bunch— and the week’s namesake— is Frieze Los Angeles.

One hundred and one galleries from around the world have come together in a makeshift convention space at the Santa Monica Airport, made up of industrial sized tents, temporary walls, and carefully placed portable bathrooms that, when constructed together, almost feel like permanent spaces. If you’ve ever been to a convention where a large space houses multiple booths selling anything from sports cards to the latest trends in dental care —it’s like that, but with incredible contemporary art.

This fair is indicative of the glamour and decadence that one would expect from an event selling pieces ranging from five thousand dollars to just north of a million. There are also big-named brand sponsors, high-end bars, and an admission price to fit. Friday preview tickets were $215, while Saturday and Sunday tickets were $80 with limited $40 student tickets (at the time of this writing Sunday student tickets are still available).

One might argue that the fair is cost-prohibitive to working-class appreciators of art, yet Frieze has been making efforts to provide free passes to schools and organizations, allocate a larger amount of discounted student tickets, as well as other efforts to be more inclusive. All of this makes for an opportunity to see work you’d normally only see in a museum, complete with the rising contemporary stars of the art world all in one place.

Here are a few highlights:

MARIANE IBRAHIM GALLERY

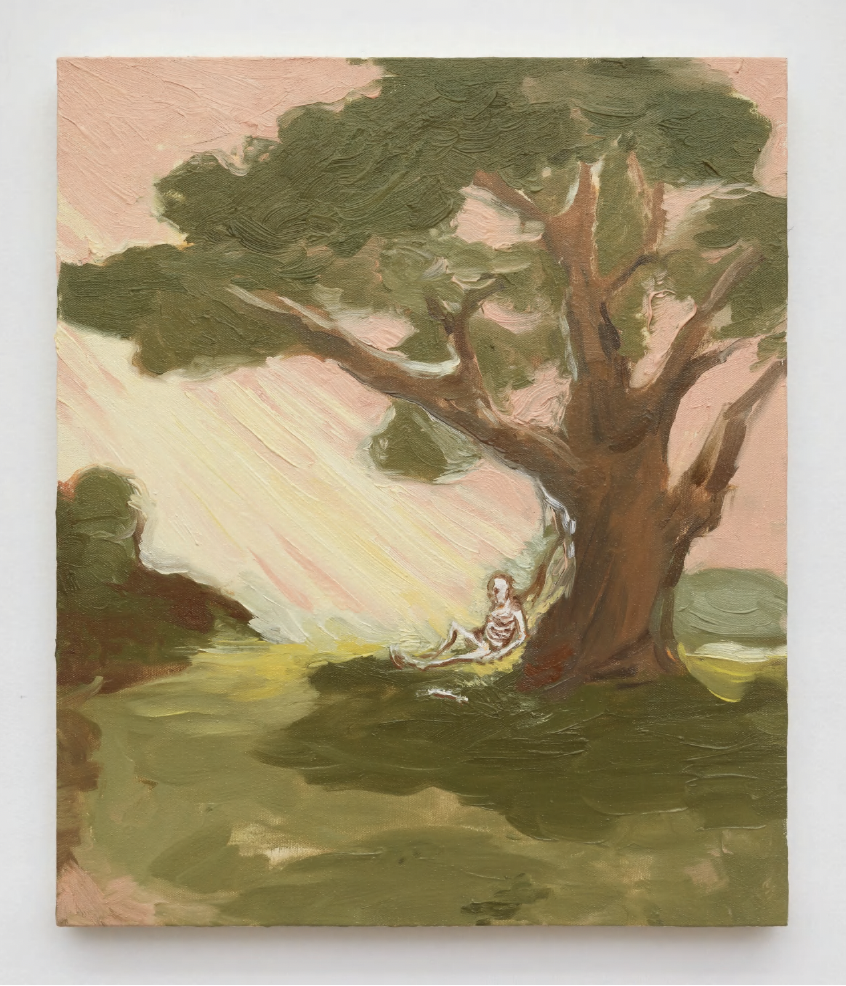

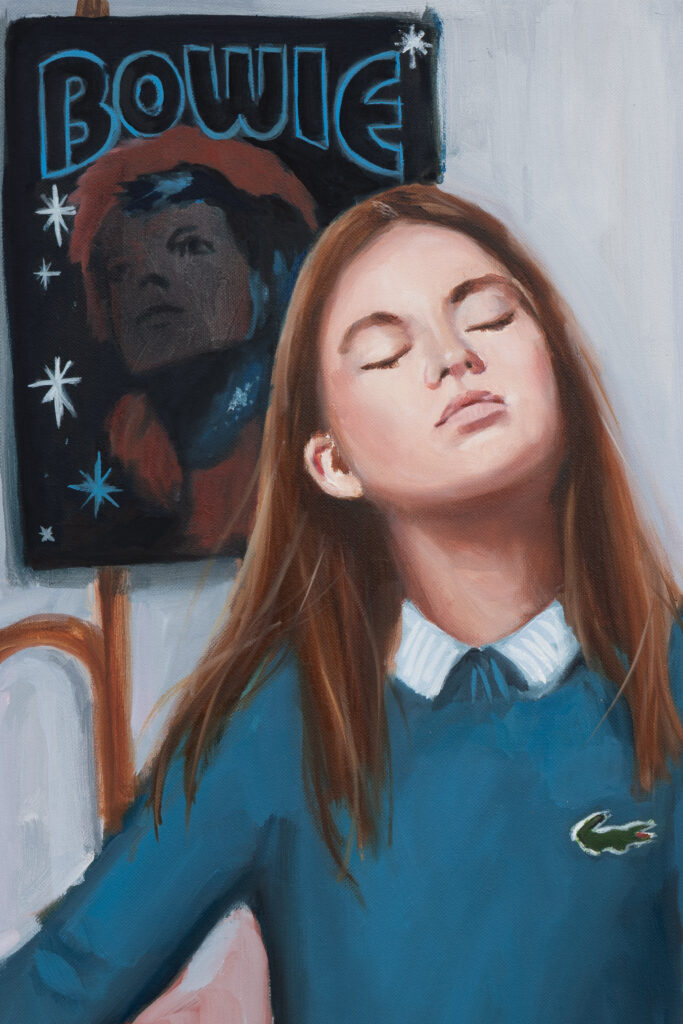

Starting at Mariane Ibrahim Gallery’s booth was a beautiful series of paintings by the Haitian American artist Patrick Eugène. The references pay homage to Abstract Expressionism’s philosophies and gestural brushstrokes, creating deeply evocative scenes of quiet emotion. Dreamy depictions of Black people in everyday situations—dining at a restaurant, strolling through the park, or having a morning coffee pair together— frame a world where one can appreciate the quiet and beauty of life.

Aptly titled, Serene, one painting portrays a woman sitting at a restaurant table, either prior to ordering or while waiting for her food. The colors —muted, darker blues, greens, and browns—blend to create a space that is familiar yet nondescript. The woman, sitting in reflective silence with her eyes closed, appears thoughtful and beautiful. Everything about the work draws the viewer in.

It’s interesting to note that while Abstract Expressionism was one of the first movements of art that was truly a distinctly American style, it also helped pull the center of the art world away from France’s stronghold and squarely into the hands of New York City. Haiti, too, was once (quite violently) in the hands of the French, and by painting Black people in scenes of beauty and quiet grace, Eugène’s work subtly redirects power to his Haitian heritage.

CHARLIE JAMES GALLERY

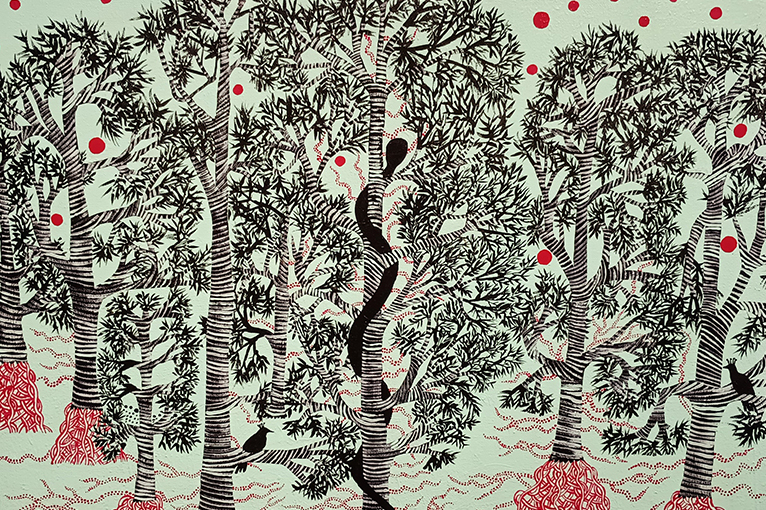

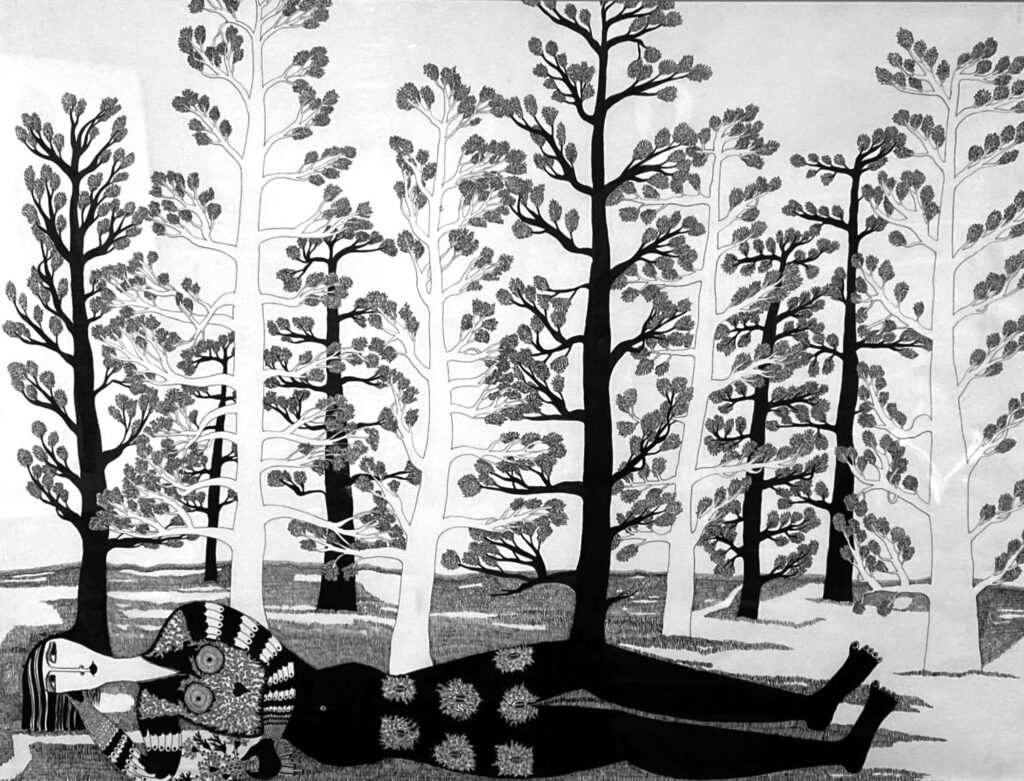

Another must-see is Charlie James Gallery’s booth, exhibiting a duo show of Ozzie Juarez and Jackie Amézquita. This year, the gallery is pulling triple duty, with multiple exhibitions closing this week in their Chinatown space, and a booth at Felix Art Fair in Hollywood. Both Frieze booth featured artists are having breakout moments in Los Angeles and beyond right now. Juarez participated in the much-celebrated 2024 group show, “At The Edge of the Sun” at Jeffrey Deitch Gallery, and both artists also had well-received solo exhibitions with Charlie James Gallery in Los Angeles.

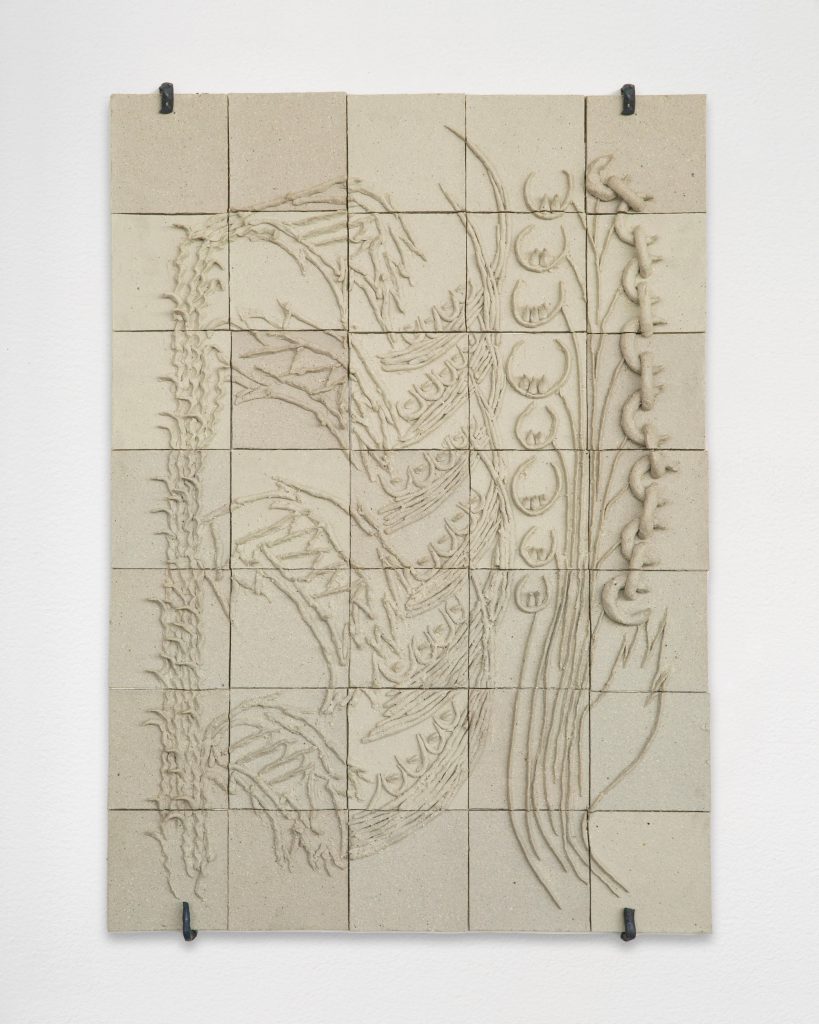

Continuing her solo show series, Amézquita creates work that embrace pre-Colombian and indigenous practices for her tile and ceramic pieces, celebrating both her culture and womanhood. Her handmade pottery and stonework vessels evoke the five stages of regeneration, and are thoughtful reflections on notions of community and collective ancestry.

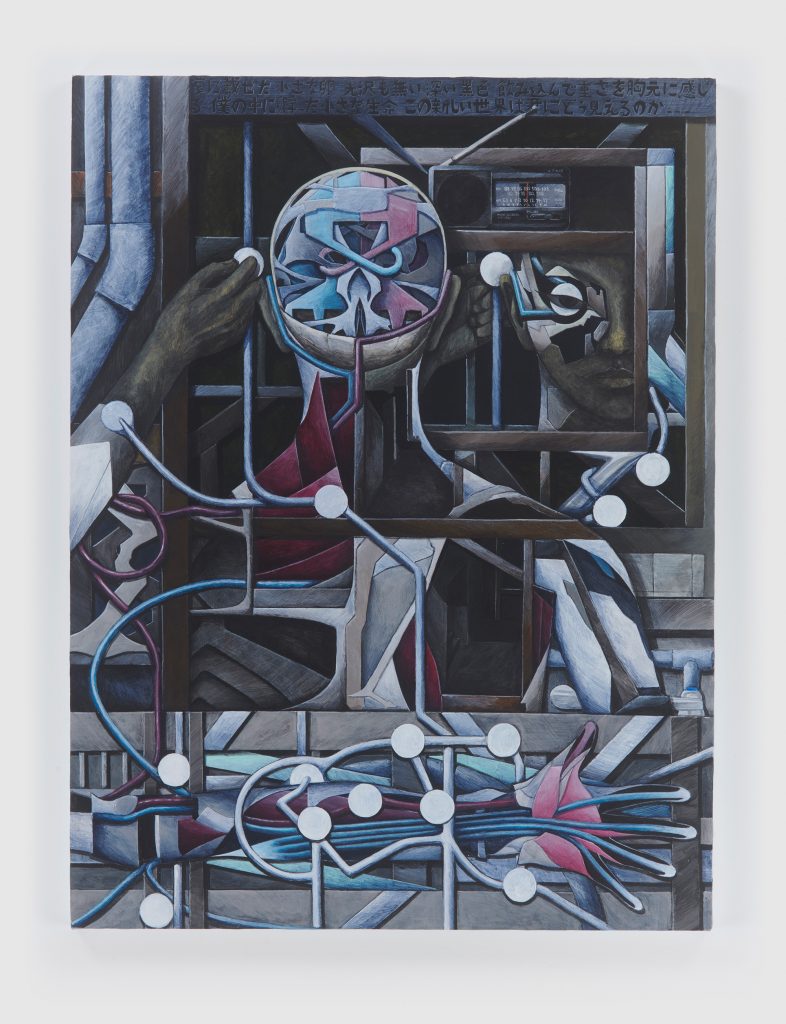

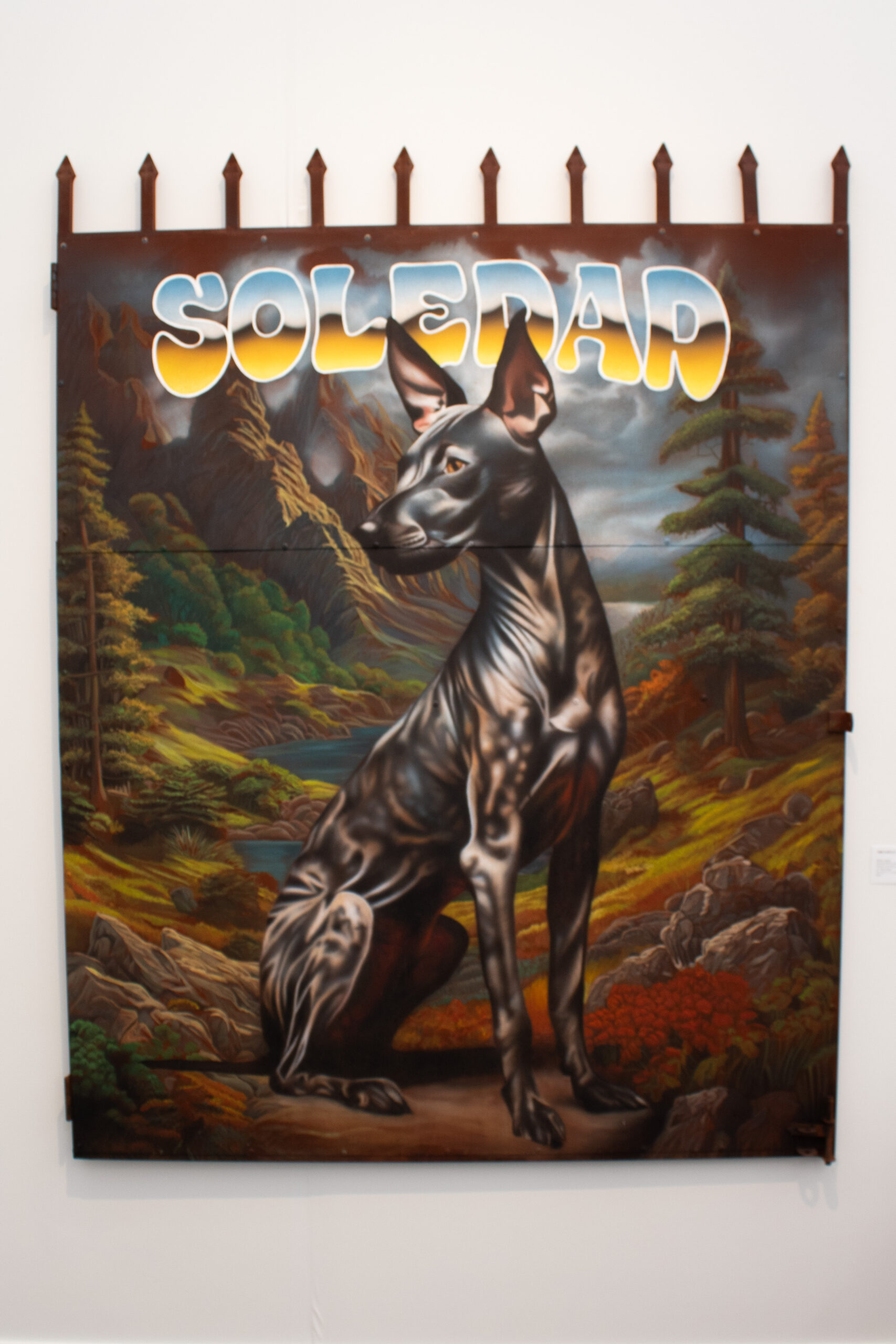

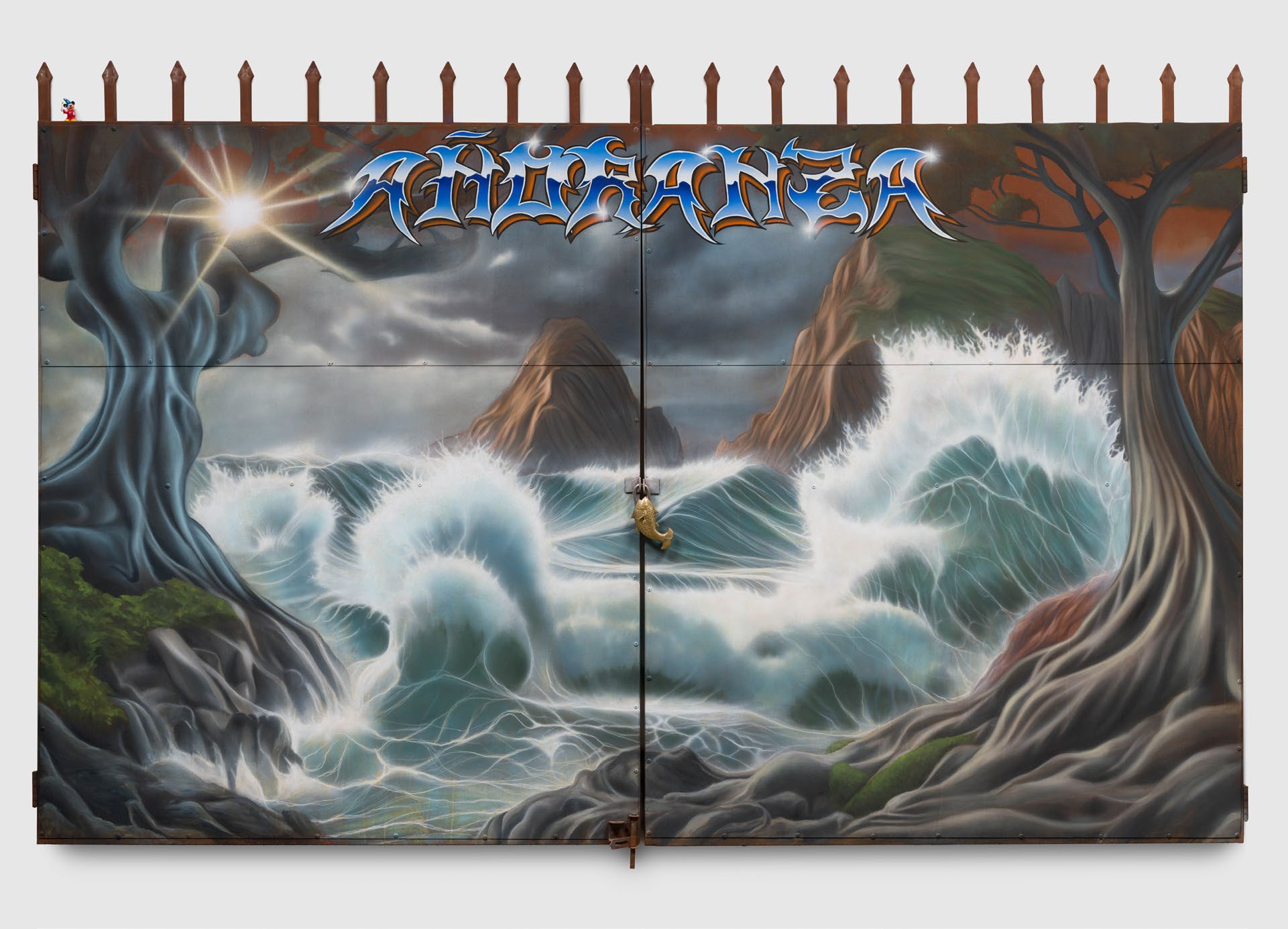

Juarez’s mixed-media paintings — part of his ongoing solo show series— present colorful scenes and images painted on fabricated metal gates. The imposing nature of spike topped metal gates, often found in industrial corridors or alleyways, is juxtaposed with images that either celebrate Mexican heritage— like the piece Soledad, which features a Xolo dog sitting majestically in a mountain scene— or portray scenes one would find in fantasy novels or cartoons, like the very large double-panel Añoranza. The paintings can either soften the opposing nature of the gates or serve to repurpose them into portals into another world, hiding the treasures within. In his work, Juarez reconceptualized and uplifted distinct aspects of cultures and communities that are quite powerful.

Beyond the booth, both artists are presenting large-scale pieces outside the main fair hall as part of the Frieze Projects “Inside Out” program curated by Art Production Fund.

FRIEZE LOS ANGELES IMPACT PRIZE

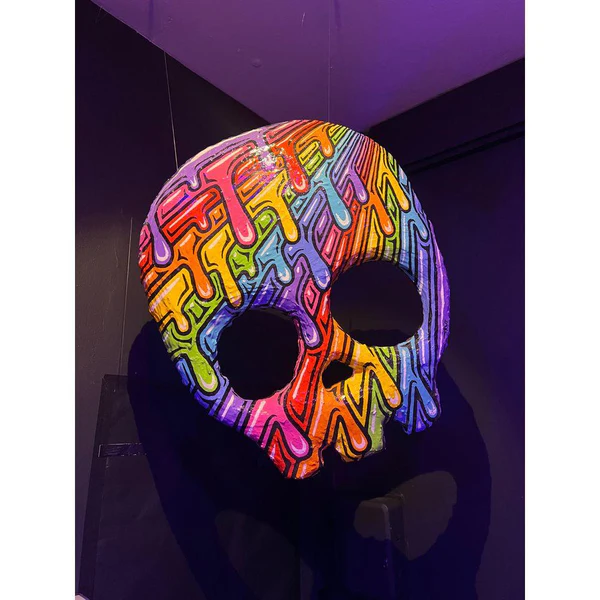

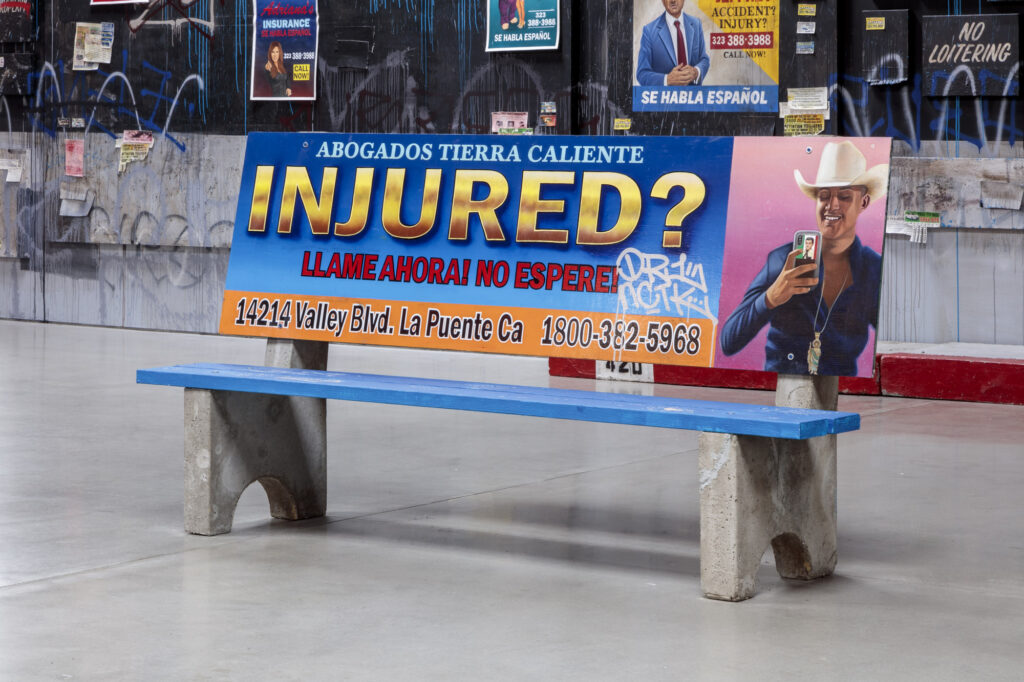

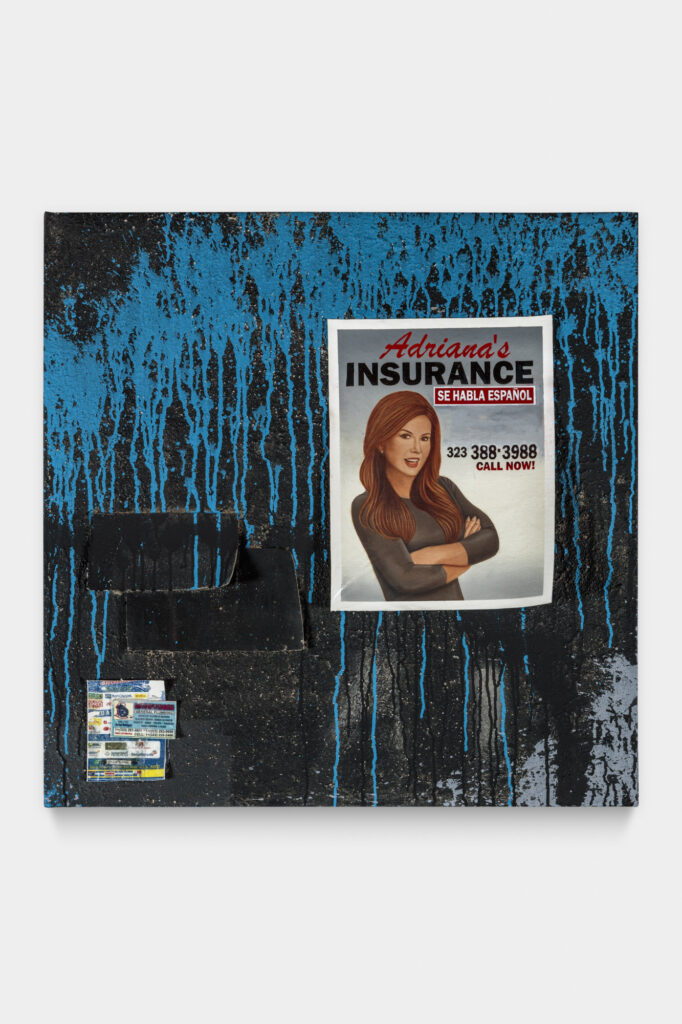

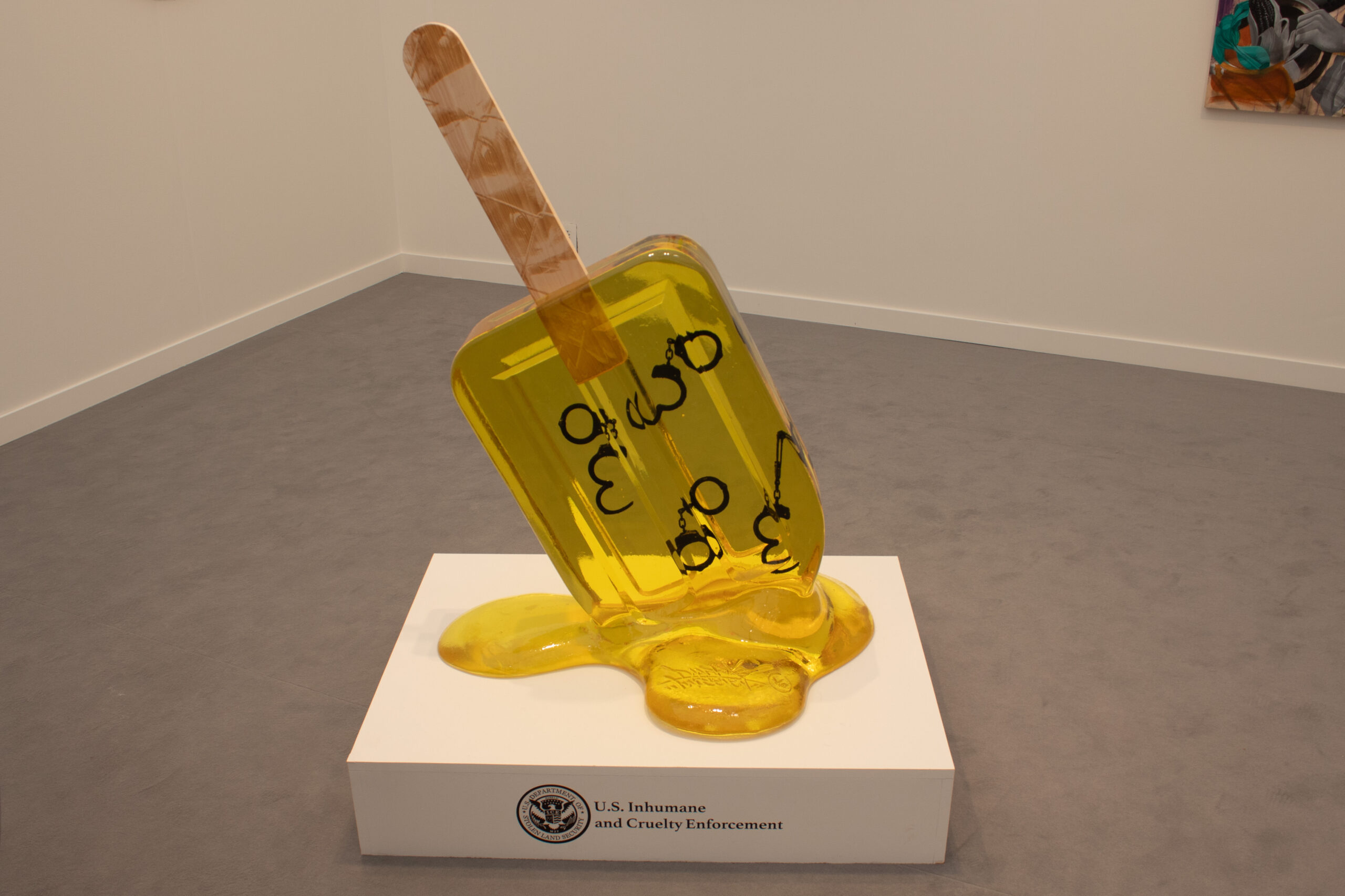

No fair would be complete without prizes, and this year The Frieze Los Angeles Impact Prize was granted to Victor “Marka27” Quiñonez. This award celebrates an artist whose work has made a profound social impact, with the winner receiving a $25,000 award and a solo exhibition space at the fair. Quiñonez used the opportunity to present his I.C.E SCREAM series, a profound exploration and confrontation of the United States’ ugly history with immigration and the resilience and beauty of the primarily Latino people caught in the crossfire. Sculptures, paintings, and mixed media pieces adorn the installation, with a central melting popsicle revealing handcuffs within. At the base of the installation, referring to the scene of caged migrants on the stick, a label reads “U.S. Inhumane and Cruelty Enforcement,” and is easily the fair’s most powerful representation.

CASEY KAPLAN GALLERY

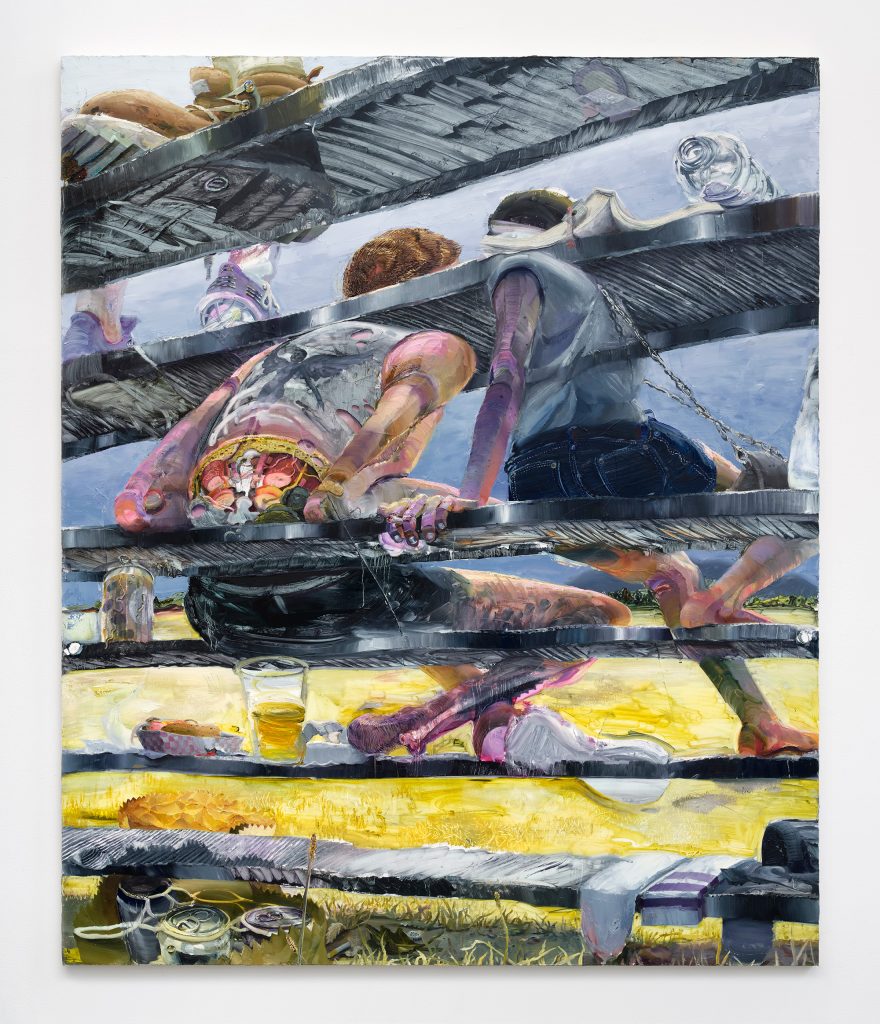

The absolute star of Frieze is Sydney Cain’s deeply haunting and introspective paintings on view in Casey Kaplan Gallery’s booth. Shadowy, monochromatic images tell stories of the dark histories of the African Diaspora. Each painting depicts a group of people shrouded in shadows, with Cain seamlessly blending detailed figures into the void, as the void simultaneously transitions into figures. Using deeply expressive, somber faces, they also seem to evoke feelings of shared wisdom in Currents Never Die. Here, an authoritative woman offers guidance to the other figures, with the closest slightly bowing his head in reverence. Two less defined figures possibly representing those yet to come, are receiving the tools they need to carry the torch. By tapping into the strength and power of ancestral record, Cain is capturing a world beyond the terrestrial and into the afterlife.

In another standout painting Undercurrents, a large group of people travel through dark waters on a small boat that can barely contain them. Yet amongst the grave faces, a small child stares directly at the viewer with a resolute gaze, a subtle yet profound blueish light emanating from her dress and hair, piercing the surrounding darkness. This ethereal light in the darkest of seas is a beacon of hope.

It’s that very same hope, evident in Cain’s work and in many others, that makes Frieze an experience worth having this year. With the aftermath of the fires in both the Palisades and Altadena still fresh in many Angelinos’ minds, one might wonder if it’s too soon for events of this scale in a city that has yet to begin rebuilding, let alone clear the rubble. However, it was clear—from efforts to incorporate fire relief in the event, to many artists donating prints to the Grief and Hope fundraiser, to the mindfulness of attendees, as well as the jobs and economic benefits these events bring—- that art remains a vital means of fostering community. Whether you are a collector, a casual art enthusiast, or an art student seeking inspiration, there is something for everyone.

Finally, while the fair may feel a bit daunting to navigate with the sheer number of galleries on view, the entire space can be explored in about two to three hours —even with frequent stops for reflection when a work catches your eye.

Freeze Los Angeles

February 20-23rd, 2025

Santa Monica Airport

3027 Airport Ave Santa Monica, CA 90405

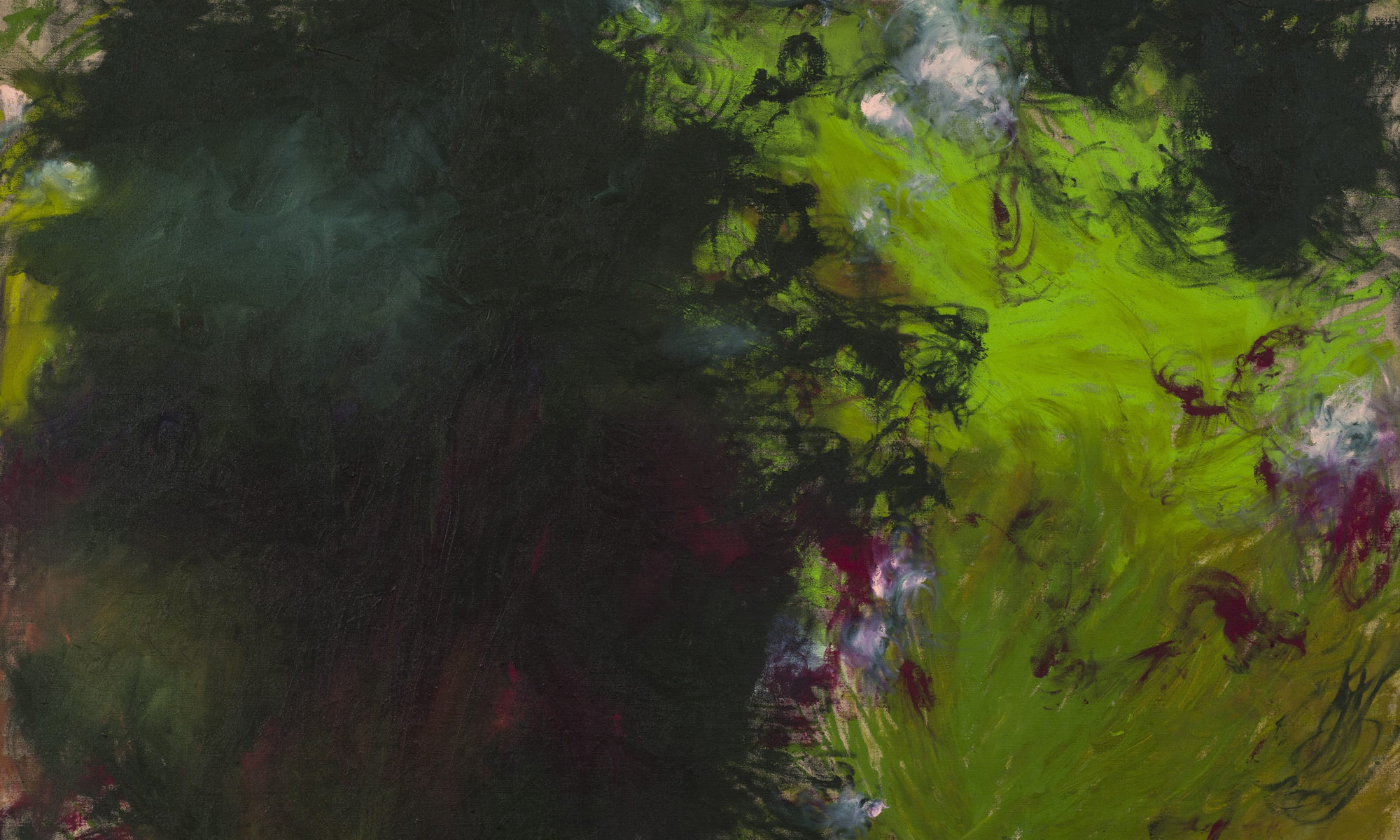

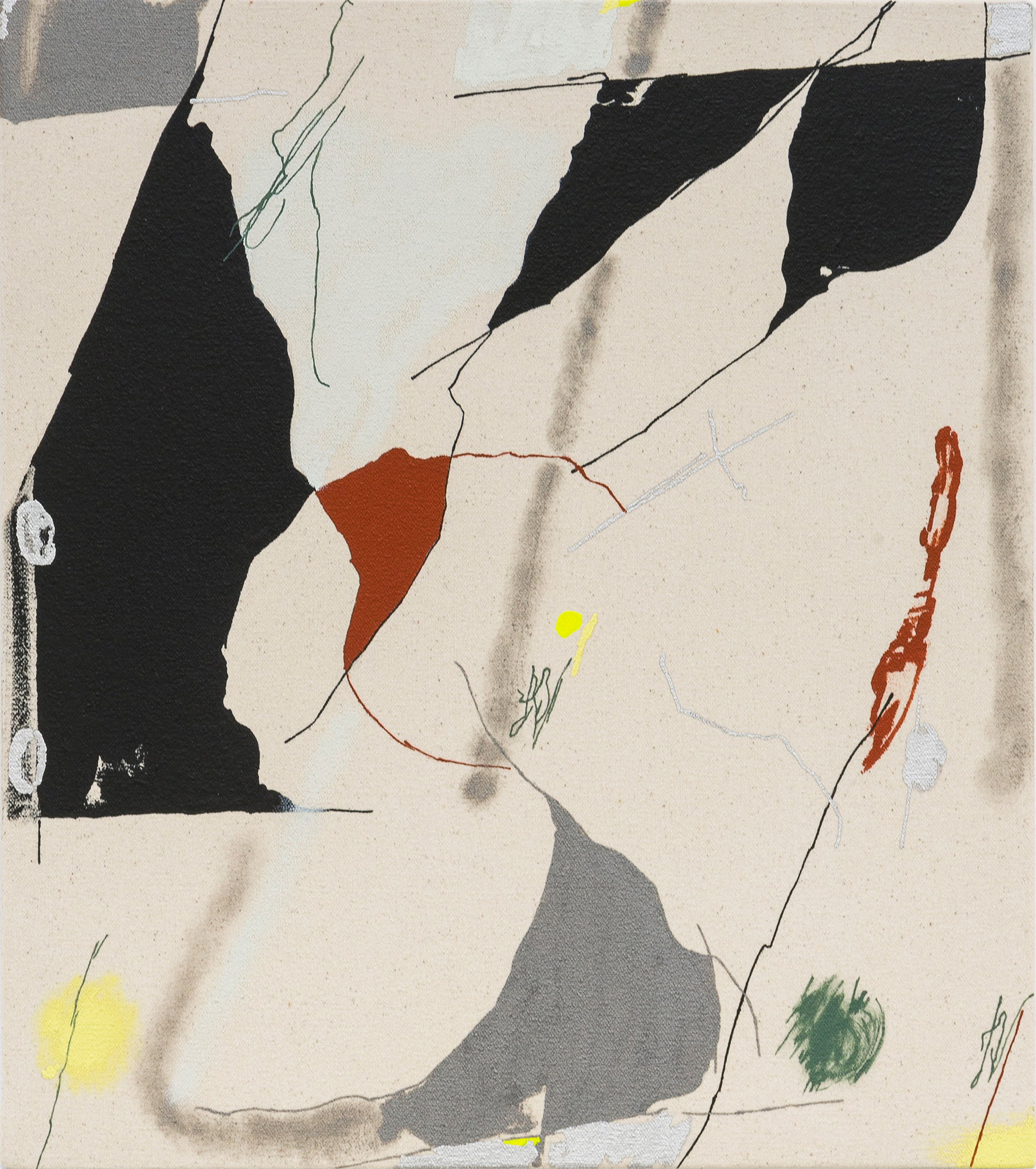

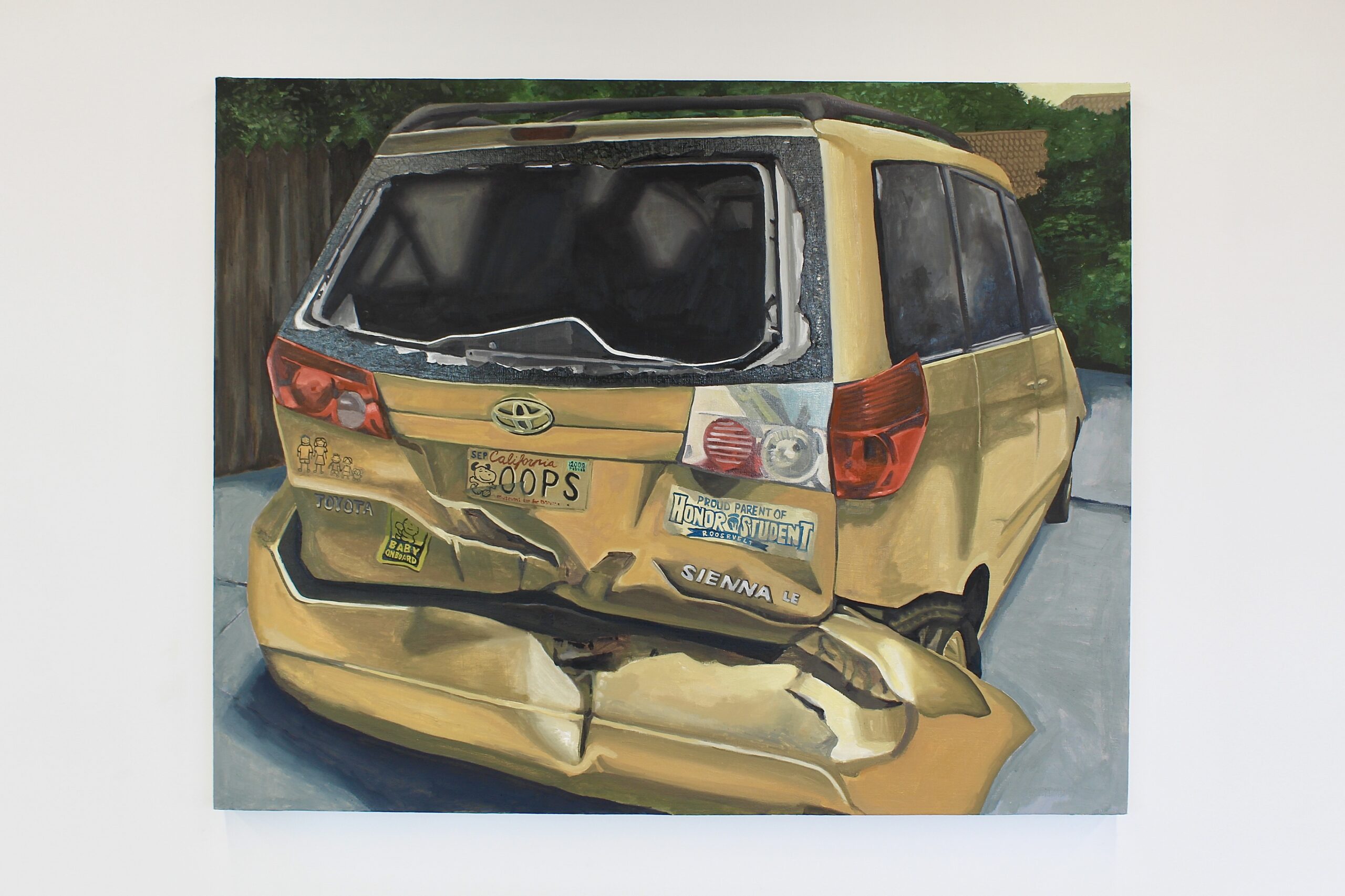

Kevin Yuan, Pacific Coast 27, 2024. Oil on canvas, 48 x 48 in. Image Courtesy of Billis Williams Gallery.

Kevin Yuan, Pacific Coast 27, 2024. Oil on canvas, 48 x 48 in. Image Courtesy of Billis Williams Gallery. Kevin Yuan, Hillside Glass, 2024. Oil on canvas, 40 x 30 in. Image Courtesy of Billis Williams Gallery.

Kevin Yuan, Hillside Glass, 2024. Oil on canvas, 40 x 30 in. Image Courtesy of Billis Williams Gallery. Kevin Yuan, Pacific Coast 7, 2024, Oil on canvas, 72 x 48 in. Image Courtesy of Billis Williams Gallery.

Kevin Yuan, Pacific Coast 7, 2024, Oil on canvas, 72 x 48 in. Image Courtesy of Billis Williams Gallery. Installation image of Kevin Yaun: In Between Walls at Billis Williams Gallery, 2024. Image courtesy of Billis Williams Gallery.

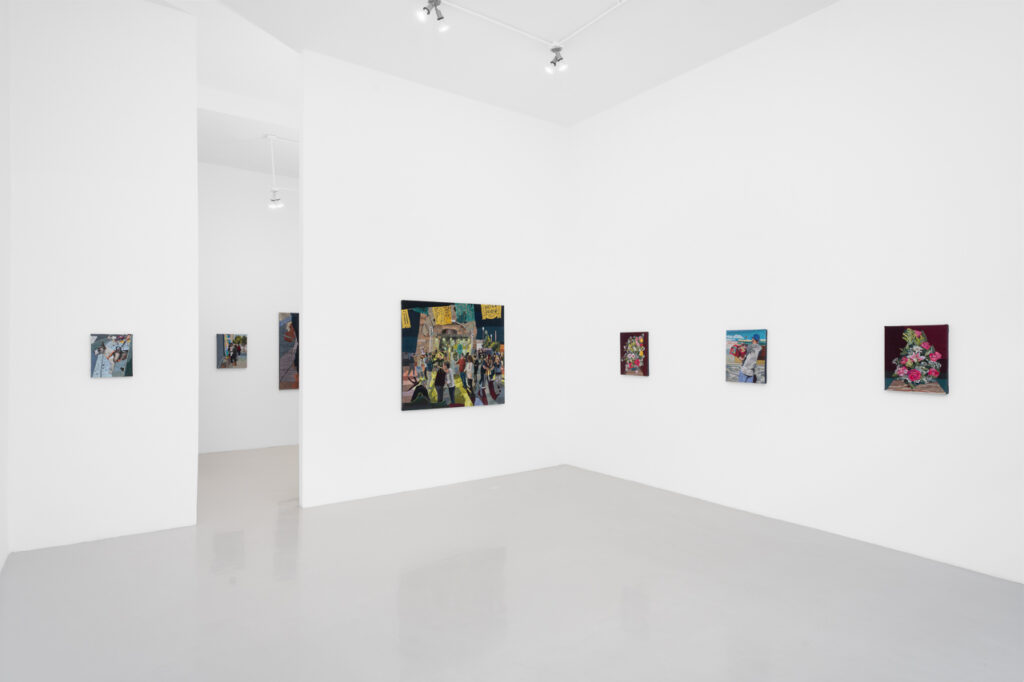

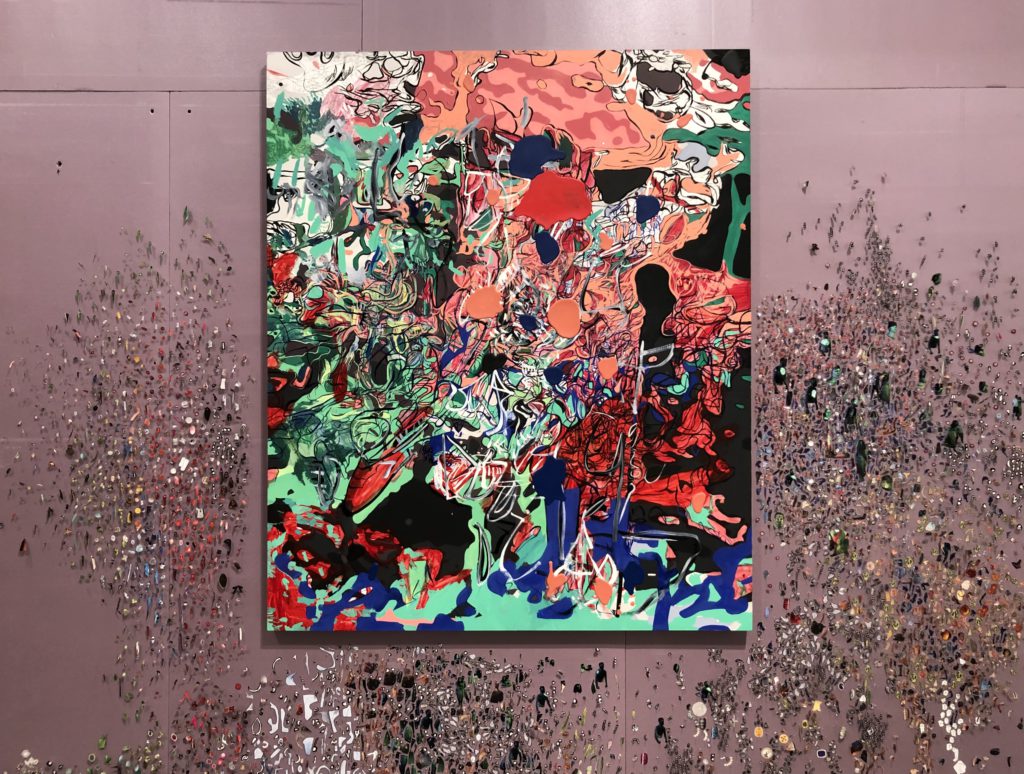

Installation image of Kevin Yaun: In Between Walls at Billis Williams Gallery, 2024. Image courtesy of Billis Williams Gallery. Installation image of Kevin Yaun: In Between Spaces with At Home, 2024 located at second from the right. Image Courtesy of Billis Williams Gallery.

Installation image of Kevin Yaun: In Between Spaces with At Home, 2024 located at second from the right. Image Courtesy of Billis Williams Gallery.