One of my favorite half-truths in the art world is that there really isn’t anything new, just variations of what’s come before. It’s true that what might appear undeniably “new” can be endlessly dissected into “old” components, merely recombined. This seems like a dispiriting process, but it reveals another truth: that something exists apart from the components themselves; something that develops relationally, between them.

That same principle applies to exhibitions, too. Based on how works are grouped, aligned and contextualized, an exhibition can charge art objects with new meanings, evoke ideas and feelings between objects, and summon themes from a group of them. The power in this unseen relationality—the connections between things—often makes the difference between a great show and a show merely with great art.

In “We are all guests here,” a group show at Bridge Projects about the Jewish tradition of Sukkot, the difference is clear. Sukkot commemorates the time the Jews spent wandering the desert after being liberated from slavery in Egypt, and is celebrated in a “sukkah,” which is a temporary walled structure of foliage resembling the shelter that once protected them. Each work in the exhibition was selected or created in response to the holiday, often through the motif of the enclosure. What emerges from that group effort is a meditation on tradition, time and human vulnerability that is so layered and moving, it appeals to far more than strictly religious interests.

Much of the show’s success comes from how it cultivates not only a deep sense of human history, but a heightened awareness of the present passing of time. In SaraNoa Mark’s warped and rectangular abstractions of carved clay and stone, for example, there is something both ancient and tender, like seeing humanity’s first marks on the earth. And like the glass vessels of her “Prayer for Rain” series, they don’t fit the logic of artifacts, but conjure the feeling of them. Mark’s clay and stone works are cleverly placed nearby Brody Albert’s found photos of desert rock formations, which are faded to near oblivion. Albert re-reframed the photos to include their un-faded edges, indexing decades of sun exposure—turning time into subject, image into object.

A sense of human history and sensitivity to time comes from ritual, too, not just objects. In a video-installation around the corner from Albert’s photos, a procession carries bouquets down a desert road. To a dirge, they walk, they perform a ceremony, they lay on the earth. Mira Burack, the artist behind Sacred Bouquet (2021), intercut the scene with closeups of local insects and flora, elegantly conflating the cycles of nature with the repeated actions of ritual, and what each carries through time.

Almost like a ritual might carry something ancient, many objects in the show also combine and confound past and present, old and new, permanent and temporary, often through contemporary technology. Adam McKinney’s Shelter in Place (2021), for example, pairs augmented reality with tintypes, an early form of photography common in the nineteenth century. Viewing the antiquated scenes through a smartphone, their subject steps into the present. Other artists used 3D printing, like the artist duo Rael San Fratello, who used the process to make their Ombre Decanters. From an ash-colored base, each vessel blooms into such intricate geometry that they resemble something both computer-generated and artifactual. Brody Albert also used 3D printing in his series “We Buy Houses” (2021), in which he recreated weathered and discarded objects in wood. After balancing the objects on scaffolding and dyeing the entire structure the same color, the objects merge—precarious fuses into permanence, temporary becomes totemic.

The ways in which these works overlap and interact—which invite the viewer to simultaneously think of the past and the present passing of time—create some of the show’s most compelling effects. “We are all guests here” bends the arc of human history inward, allowing the viewer to commune with past generations, seemingly all at once. And as an awareness of the past and the passing of time grows, so does a commensurate awareness of impermanence, both as a matter of personal experience, and collective. In this context, the touch of past generations—through the long, branching, iteratively-twisted arms of ritual and tradition—feels increasingly like a comfort. Even as an atheist, I nonetheless felt the force of the religious tradition emanating from these works.

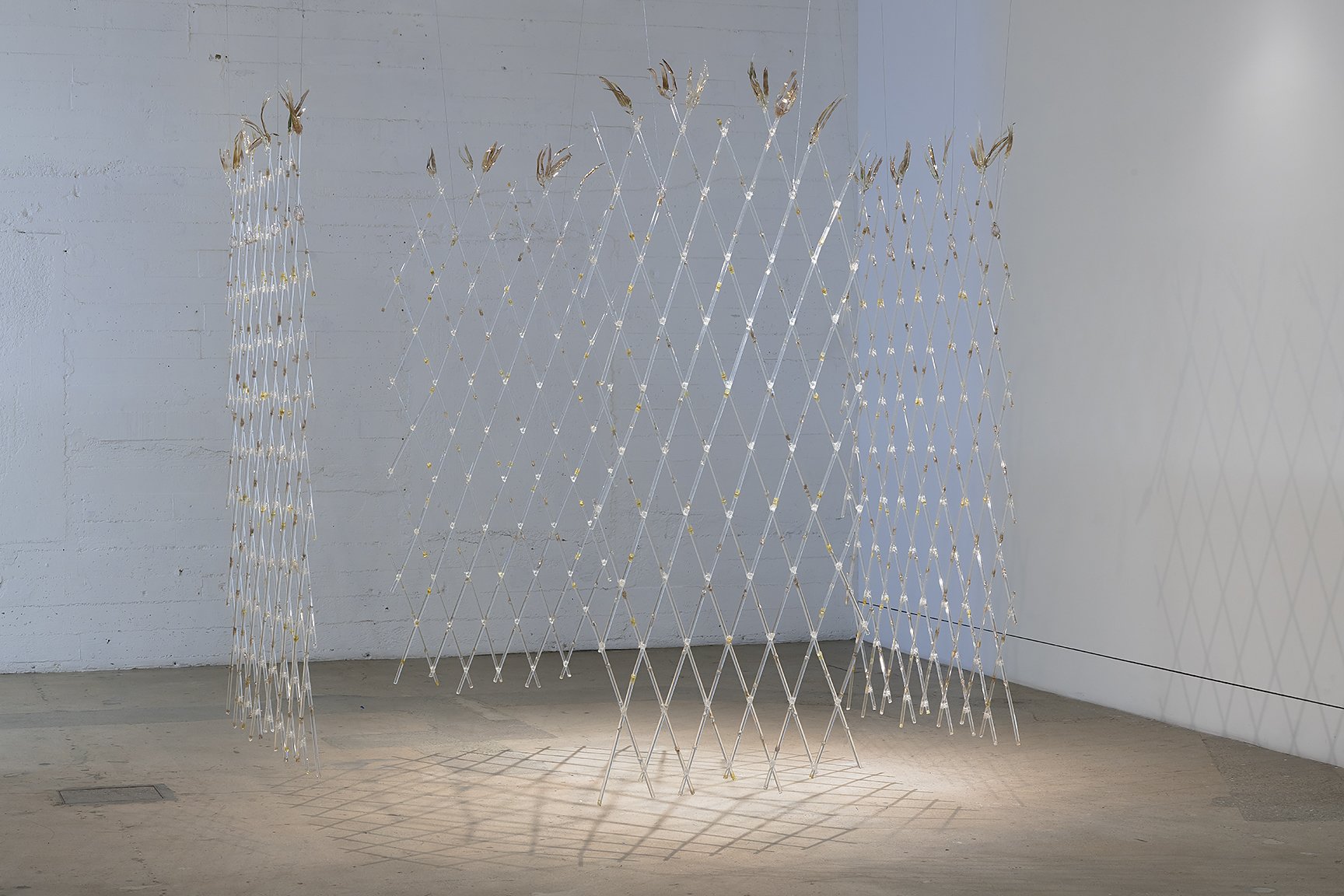

But there are no simple statements in this show. Even when it stirs compassion, it’s no feel-good or easy exhibition. Its response to Sukkot is challenging, and its focus on the sukkah, that emblem of shelter, is more contemplative and poetic than it is protective. For instance, sitting inside Rael San Fratello’s Sukkah of the Signs (2021), a temple-like structure shingled with the cardboard signs of the homeless, you can see its exposed construction and smell its freshly-cut lumber. But among the implied presence of the many without shelter, those percepts take on a darker note. Likewise, Adam McKinney’s Shelter in Place encircles its viewers with tintypes, swirling tree branches, floating video displays, and a dancing, augmented-reality apparition, but the space feels more haunted by its past: the sole black man in each tintype stands next to a cop car, gravestones, and a trailer with “cotton belt” emblazoned on it. The exhibition’s poignant socio-political commentary occasionally drifts into the unearthly, too. In Jenny Yurshansky’s We Are All Guests Here (2021), for example, its floating, latticed walls of glass embody the ethereality of a spiritual object, yet appear fragile and unwelcoming.

The show’s simultaneous contemplation of the past and the religious object is further complicated, subtly, by several works that turn attention inward—by how they confuse the object with what is seen through the object. In another piece by Yurshansky, Blacklisted: A Planted Allegory (Memoriam) (2015), a shadowy landscape droops from two nails. As the voile gently ripples, awareness shifts from the printed image to the object itself, conflating the object with the image “beyond” it. Brody Albert similarly flattens object and vision with his Untitled (2019) pieces, in which cyanotypes of tattered window screens are framed in indigo-dyed wood. Where one might expect to see through, there is only an opaque object. Similarly, in Cuarto de Estar (Living Room) (2021), Susy Bielak has replaced the mirrors in antique dressers with photo transfers. Where one might expect their own visage, there is only past.

While I love fine art—how it lets us explore human experience through combinations of what we already know—I often criticize it for being too insular, too self-referential. What enables “We are all guests here” to accomplish so much, and why it stands out in today’s art scene, is that it speaks through a visual language understood by more than just the art world. From deep within our lived experience, it can excavate something unusual and unfamiliar, yet still feel universal. “We are all guests here,” in the way it intones human vulnerability, echoes the shape of tradition, and loops time inward, works a spell that no studio dialect could. And maybe more importantly, it teaches us—attuned to its spell—all that we should listen for when we step back into the world.

“We are all guests here”

Curated by: Cara Megan Lewis, Linnéa Gabriella Spransy Neuss, Vicki Phung Smith, and Michael Wright

September 3, 2021 – January 15, 2022

Bridge Projects

6820 Santa Monica Blvd

Los Angeles, CA 90038

www.bridgeprojects.com