With all of its flesh tones and synthetics, its re-purposed refuse, its simulations and premonitions, its wisps of human history and myth—and especially its rethinking of the body—“Durian on the Skin” feels very post-human, maybe even a little post-apocalyptic.

Before seeing the show, “Durian on the Skin” caught my interest as I wanted to see how the curator handled the dilemma that seems to arise when addressing forward-looking topics or drawing from emerging visual languages. And that is: if the work draws too much from a new or emerging visual language, it risks having no effect on a viewer, as visual languages need time to accumulate connotations and associations before the artist can go about orchestrating them for some effect. But if the artist relies too heavily on old or familiar visual languages, they risk failing to capture something essential about the forward-looking topic.

It’s easy to forget—maybe because artists have such free rein now or because art is “all subjective anyway”—but there are aesthetic decisions artists (and curators) should be making. It’s a role where they, and only they, can identify visual languages where others could not; and to surprise us, maybe even wound us, with what we know, but don’t recognize. This was just the sort of thing I found with “Durian on the Skin.”

“Durian on the Skin” was so expertly curated, and offered so many revelations in between its works, that it would be crude to categorize it as post-human or post-apocalyptic, or to categorize it at all. It does pay a lot of attention to the body, though, and owing to how its curator handled the “dilemma” of emerging visual languages, you can feel its definitions shifting.

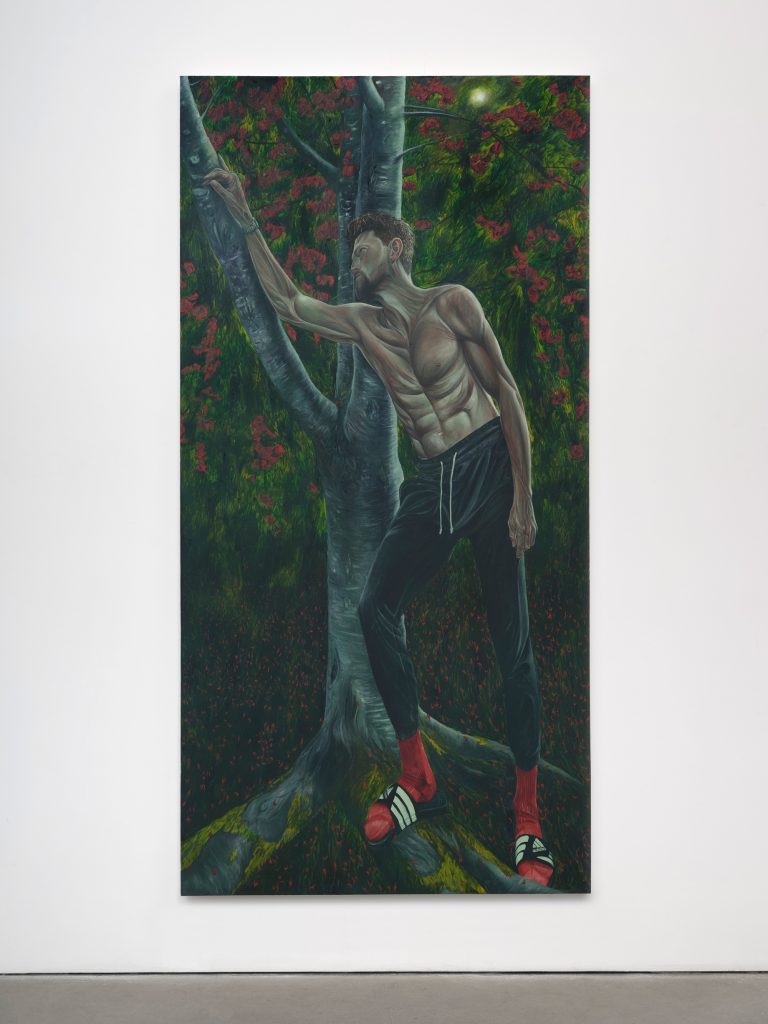

For a show interested in the body, the curator, Gan Uyeda, was apt to include a virtual reality piece. VR is known for simulating environments, but it runs another less obvious simulation: that conscious experience might not have anything to do with the material that holds it. In Rindon Johnson’s Meat Growers: A Love Story (2019), you’re guided through a forest of giant trees, you pass cloaked buildings, you glide over wet earth as if a storm had just passed. Occasionally, almost as if it detached and floated away, you remember your own body. The more immersed you become, the more you contemplate what it’s like to push conscious experience out of the material and into the immaterial.

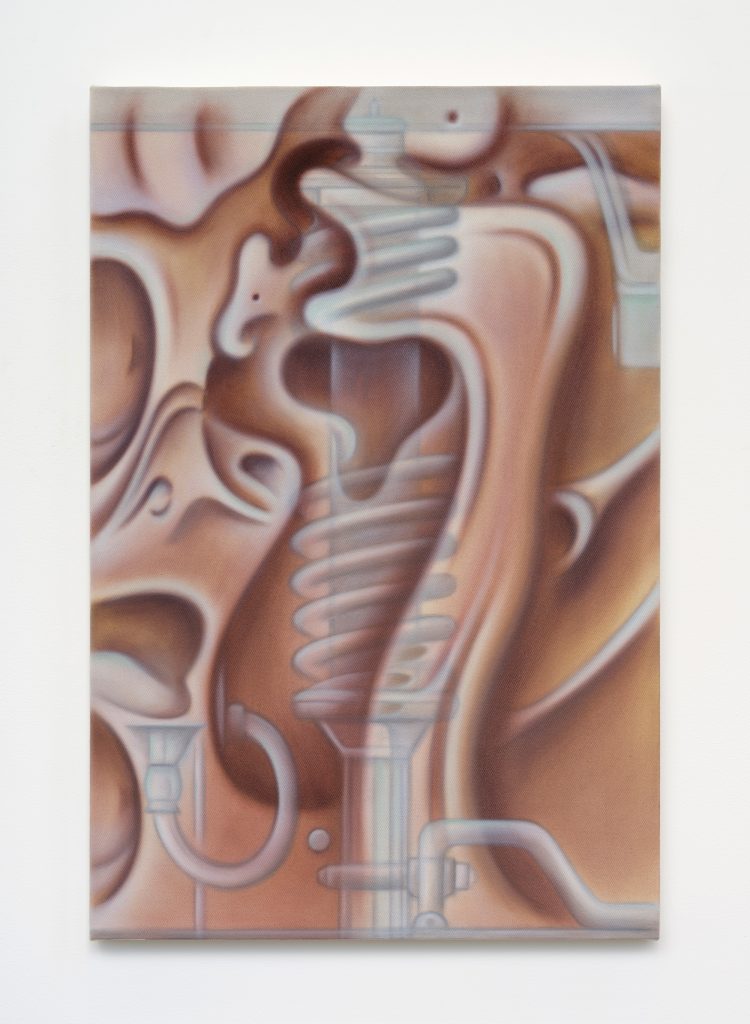

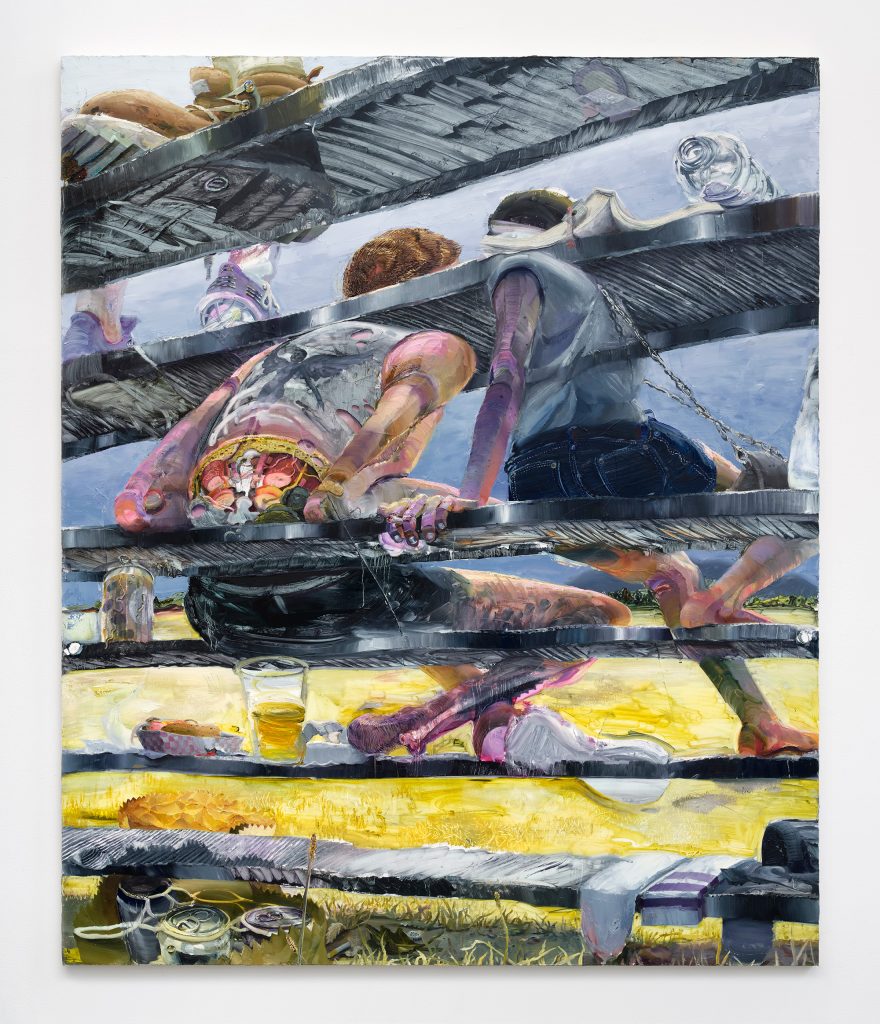

Taking off the VR headset, that meditation on the body and immateriality continues with the neighboring works. The cast beeswax torso of Kelly Akashi’s Stratum (2021), for example, quite literally treats the body as a vessel, albeit a fragile and organic one. In Gabriel Mills’ DIAMOND SEA (2022), paint flickers between material and immaterial across three panels, and its floating ethereal pane sparks an unexpected connection between painterly abstraction and virtual space. In Danica Lundy’s Late Summer Pitch (2022), bodies glitch into bleacher seats and paint eviscerates its subjects.

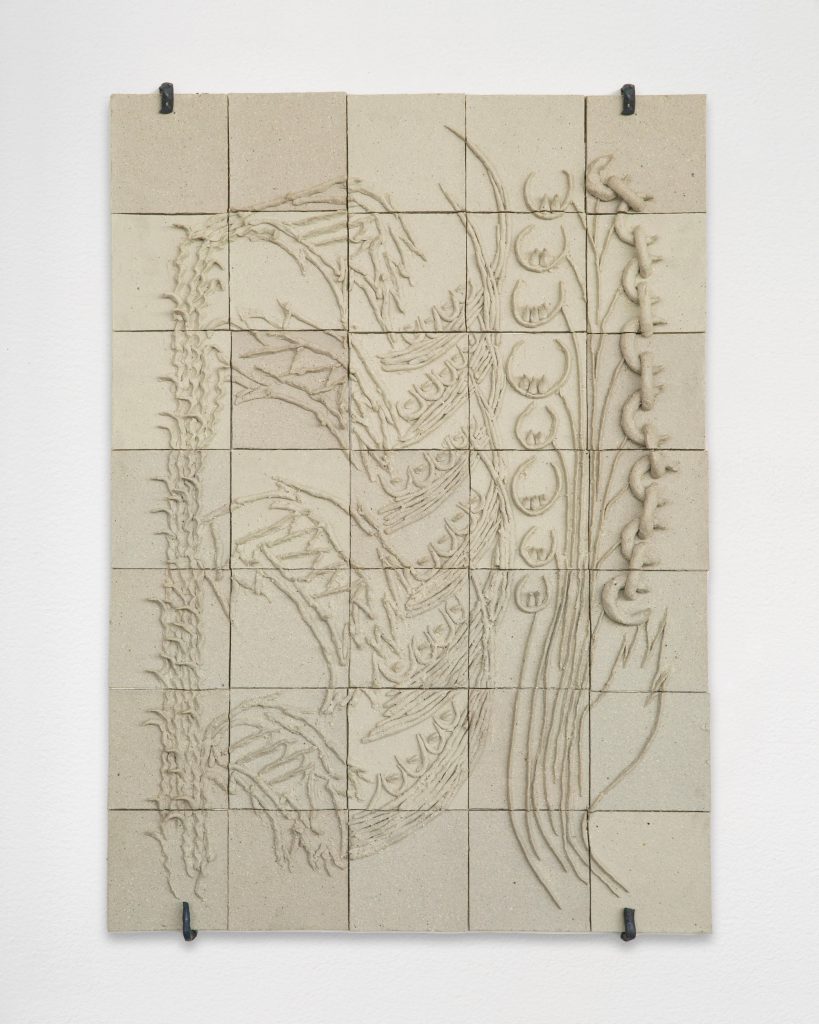

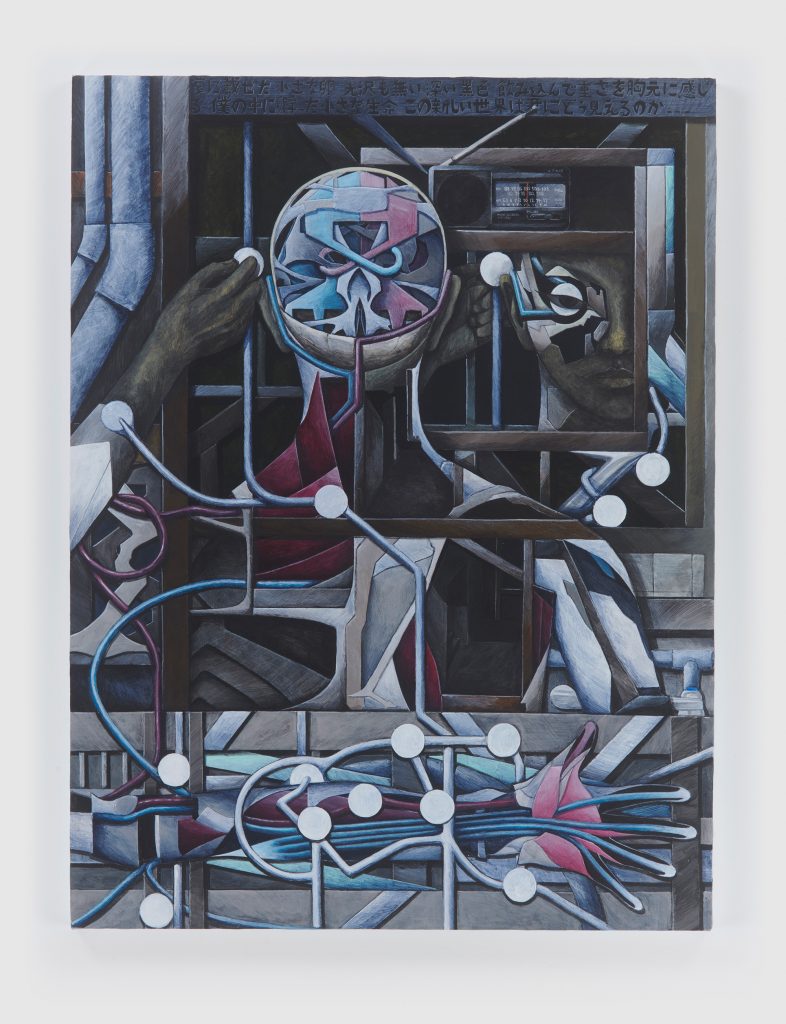

Uyeda adds subtle touches of history and myth, too. Candice Lin’s squatty and gnarled totem, Piss Protection Demon (2022), feels like history and myth have curdled into artifact. Joeun Kim Aatchim’s fish-hooked porcelain works strike a tribalistic note. Isaac Soh Fujita Howell’s schematic painting of a humanoid-as-machine, with its nod to Italian Futurism, lends a tone of past-imagining-future.

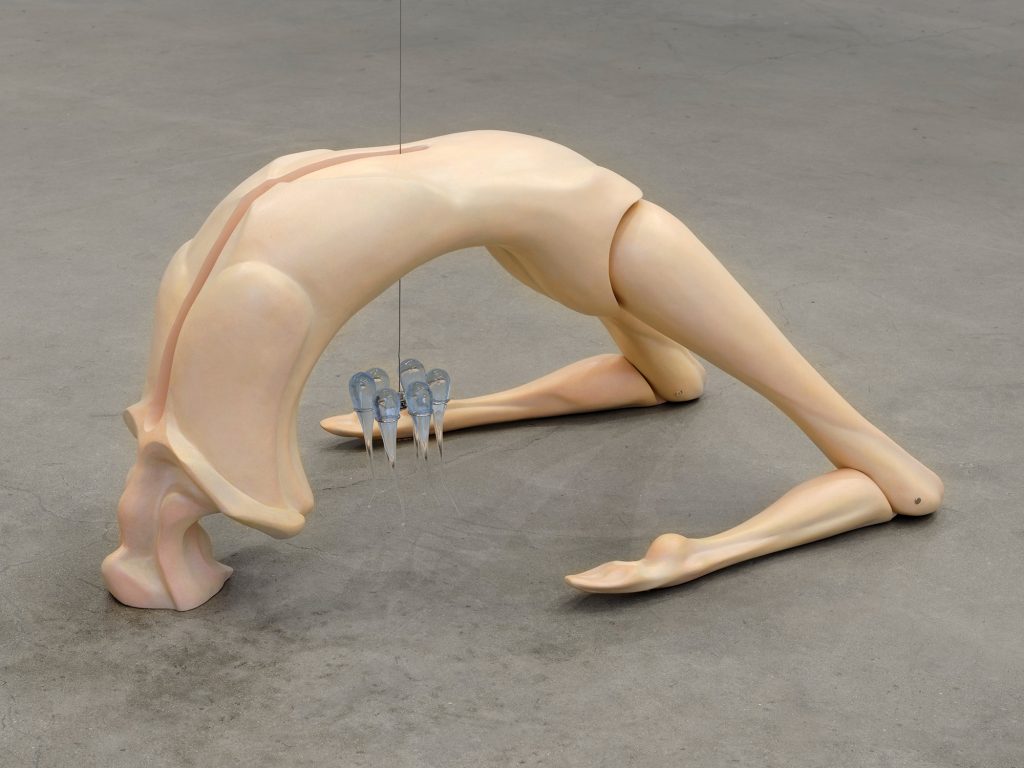

Some work, like Liao Wen’s two humanoid sculptures, made me think of my own body’s hardwiring and how it has evolved to understand other bodies. That evolved response can be as simple as wincing at another’s injury, or it could be, if you’re familiar with Boston Dynamics, as curious as the trace of empathy you feel when the researchers abuse their robots to test their balance. Wen’s figures trigger something like that. Flesh-toned and jointed like dolls, they feel like full-body prosthetics, writhing but somehow in a state of Zen. One even has a weighted wire hanging through a slot in its body. Even though the figures are neither alive nor naturally posed, I still felt my body trying to make sense of theirs—trying to transpose quasi- or non-human sensations onto itself. It’s a little eerie visiting the periphery of the body’s natural responses, but with technology like artificial intelligence and genetic modification, contemporary life seems to insist on the eerie becoming relevant.

One of Uyeda’s more counterintuitive ways of addressing the body was including works made from repurposed materials and the remains of manufactured objects. Appropriating the visual language of manufactured objects extends back at least to Duchamp’s “readymade” sculptures, but Uyeda stresses the darker aspects of that lexicon to invoke our changing relationship with fabrication and waste. In the same room as Wen’s figures are a wall-sized pelt made of porcelain shards, a spiked chimera of fur, plastic and scrap, and a plaster suit swirling without a subject. With works like these, Uyeda casts a shade of ecological desolation over the show. And in light of the show’s allusions to technology, myth and history, they sensitize the body to something both primal and prophetic.

One might say that, as we lurch through history, it’s the role of fine artists to make sense of our shifting condition by examining the corresponding changes of visual languages. But unlike other sense-making disciplines—and even some forms of art—fine art often does not offer answers or clear explanations. And, arguably, that makes it a better place for rethinking what feels so obvious or fundamentally true. Shows like “Durian on the Skin” remind me of that. Presenting the body as something suspended between myth, earth, virtual and synthetic, “Durian on the Skin” does what no dissection or system of rules could; as if, when looking more closely within, you could ever really expect to find a stable, certain, endlessly knowable thing.