Oil painting’s historical connection to wealth—and more specifically to the rise of capitalism—is not news to anyone. As the art critic John Berger pointed out, oil painting’s rise to prominence as a medium had a lot to do with its ability to express the changing worldview of the Western European ruling class of the 16th century. That is, oil painting offered a model of the world where the world could be owned, possessed, and sold—where “everything became exchangeable because everything became a commodity.” Oil painting is remarkably good at representing objects of desire as though they are real. The medium set a new standard for representation of the newly commodified objects of the world, appropriate to the forms of desire they elicited.

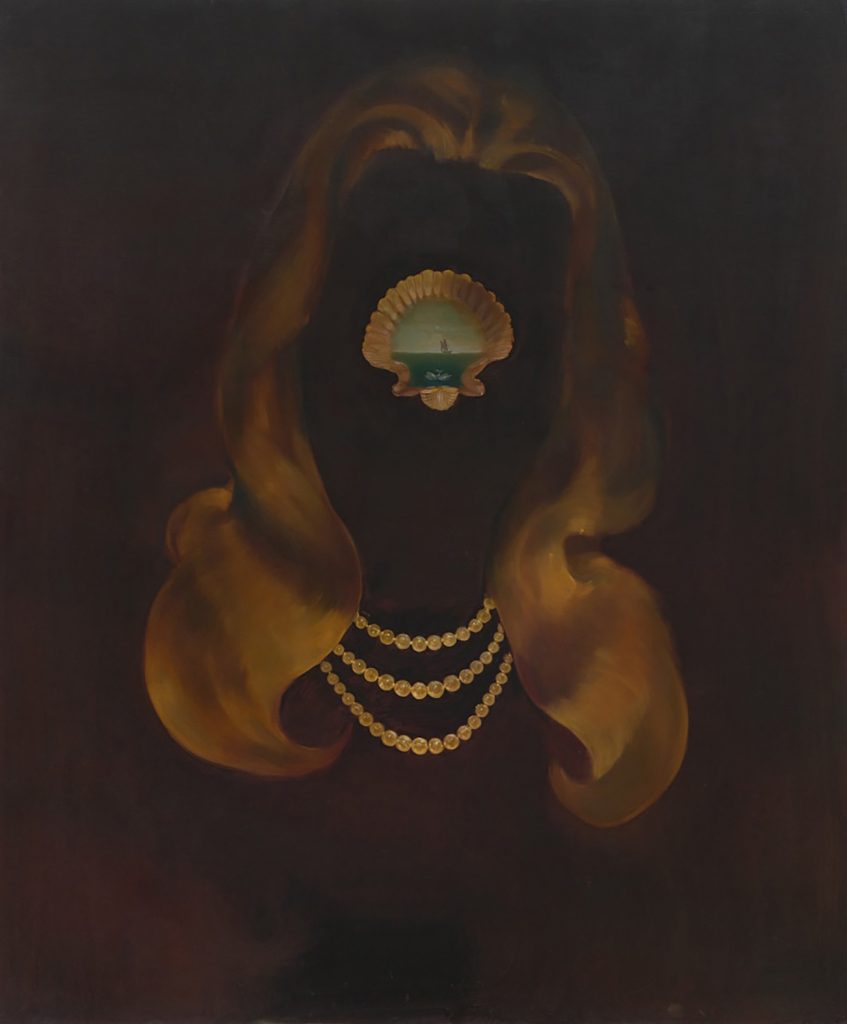

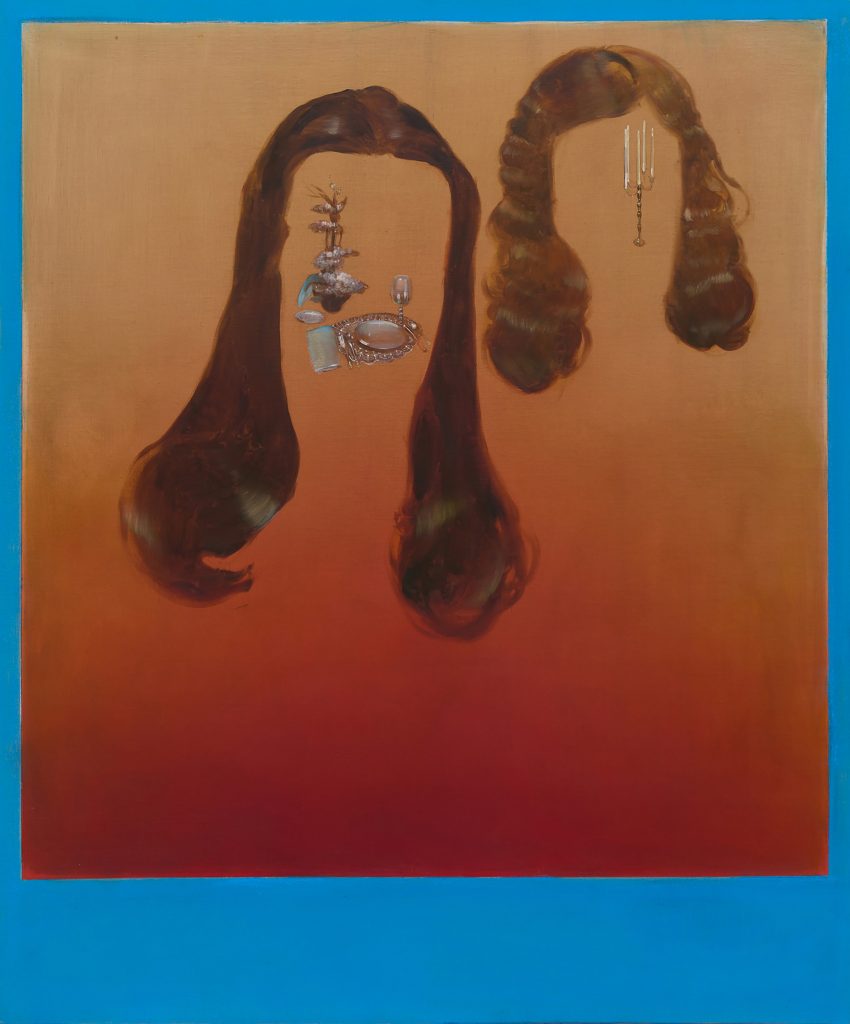

In the vaporous and multilayered paintings of “LOW VOICE OUT LOUD,” artist Rae Klein seems to be thinking about the medium’s economic history through form. The paintings of the show, all completed in 2022, range in scale from a dainty 12 by 16 inches to a mansion-appropriate 72 by 120, and take similarly mansion-appropriate hunting dogs, horses, elegantly-coiffed women, pearls, elongated silver tableware, and candelabras as their subjects, as well as other vaguely mythological landscapes and figures.

There’s also a pronounced hint of another century in these objects, even as their arrangement and spatial logic hail from the dimensionless but well-lit world of Web 2.0 graphics. This is not only achieved by her palette choices (browns, Prussian blues, ochres, sepia tones) and the visual language of the depicted objects (pearls, lockets), but also how she handles light. Everything in Klein’s paintings gleams faintly, as though struck at once by antique candlelight and an unplaceable ethereal glow. There’s a certain classical aspect in how she achieves that effect, too, especially with the accents of pure white on top of diffuse layers of paint. Seeing Klein’s candlesticks and glassy ponies, it’s almost natural to think of the glass stemware in 17th century still life painting.

The formal choices of Klein’s paintings also allow them to ask, among other questions, something like: “What might the visual expression of the object-oriented desire of the wealthy be now, in 2022?” For example, Klein’s compositions often feature richly rendered objects floating amidst non-dimensional surroundings. It’s as if the surroundings staged the objects, but were uninterested in constructing any habitable world. No one lives wherever these subjects are. This motif—of objects floating in a dimensionless void—has been one of the major ways contemporary painting seems to have incorporated the computer’s impact on the visual landscape (one might think of Rute Merk, for instance).

Klein is astute to employ that motif in such a historically-charged medium, one often designed to represent the desired objects of the wealthy. Objects floating in dimensionless voids for our consideration for purchase is by now a deeply naturalized part of our everyday visual languages. Capitalism always decontextualized and abstracted objects, but that has certainly accelerated since oil painting first began depicting hunting dogs and pearls and horses. With a lesser artist, this pairing might come off as academic, but in Klein’s work they intuitively converge through the medium.

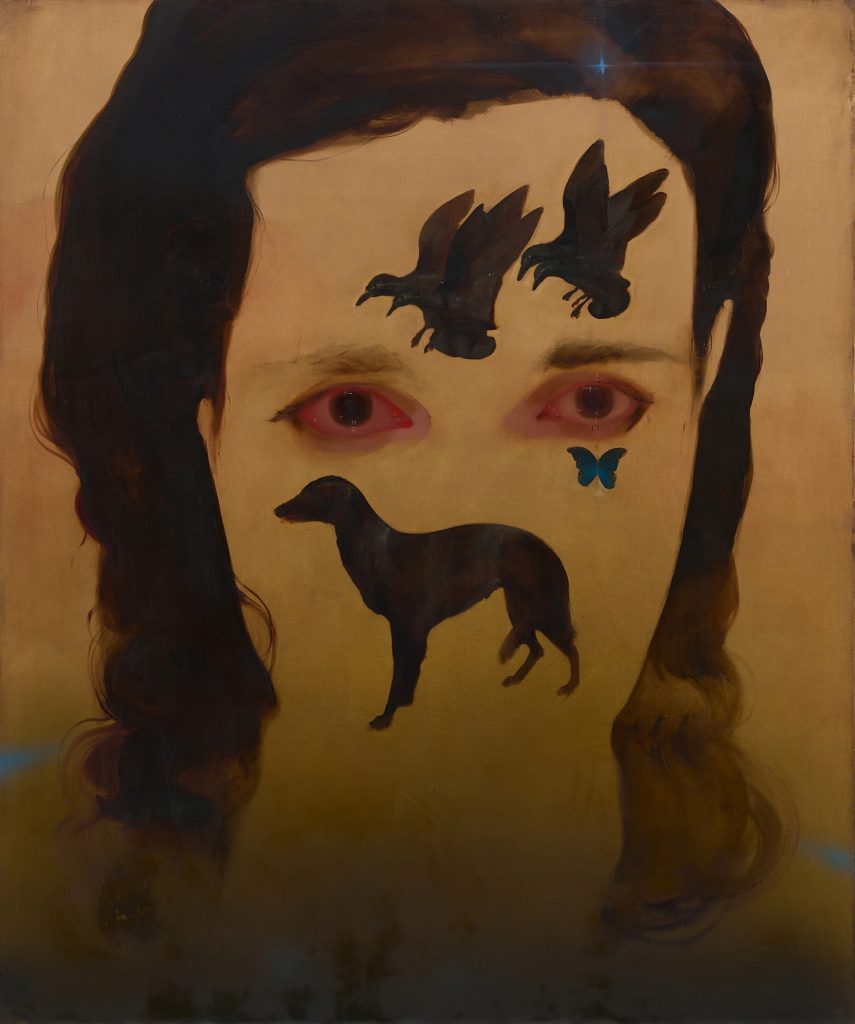

If these paintings ask, “What might the visual expression of the object-oriented desire of the wealthy be now, in 2022,” they also ask: “What does all that feel like?” The answer might be something like “eerie, lonely, discomforting, and kind of… beautiful?” One of the most interesting paintings in the show, I’ve Accepted It, And I Forgive You, seems to me to get at this question.

It’s a mid-size piece (72 x 60 inches) featuring a woman’s hair and bleary eyes floating in a goldened field, and in the space where her face isn’t: tiny ducks, a dog, and a butterfly which all hover like sticker-book style face tattoos. The piece is both lovely and off-putting, which seems connected to how impossible it is to reconcile the painting’s multiple frames of reading. Figures are staged at different scales; objects are situated in a dimensionless void; the background flickers into the space of the foreground figures, or becomes them. How are these objects and their grounds related to each other? Which, or what, is actually figure or ground? How do we understand them in space?

The painting offers tonal complexity, too. Features like the teardrop-like butterfly feel both internet-irony funny but also sincerely sad. I’ve Accepted It, And I Forgive You, like many of the works in the show, does that lovely cognitive shimmering thing good art does as it resists easy conceptualization, easy tonal categorizing, easy anything.

Surrealism is also a hovering presence here. Many of Klein’s figures offer themselves as (il)legible symbols, staged in settings whose vagueness might evoke something like “the unconscious” or “a dream.” Her multiple frames of reading, too, connect her work to Surrealism. But the way she uses them enables her to go beyond Surrealism.

Klein’s work presents a layering paradox like that of, for example, Magritte’s The Double Secret (1927) or The Human Condition (1935), where narrative “reality” is confused with what is “painted.” Like Magritte’s paintings, Klein’s draw attention to the ways pictorial illusion, context, and layering can be used to generate logically incoherent spaces. But Klein’s attention to wealth and materiality—and the odd “dimensionless” quality—takes her past this chime with Surrealism. Klein’s version of that layering paradox is not just spatial or symbolic, but also about oil painting’s history colliding with the desire, discourse, and economic structures of the present.

Like the oil paintings from the centuries before hers, these pieces would be perfect in the homes of the wealthy of their century. I can easily imagine any of these pieces in an elegant living room out of a jet-setting magazine, staged next to a fiddle-leaf fig by a white sofa on a gray marble floor. But in such settings, the painting would also smuggle in a certain unease, even as it beautifully complements the Danish teak coffee table or antique flat-knot rug. It feels naïve or a little silly to say that these paintings feel “haunted” or “off” or “poisoned,” but they do. And in that way, they feel slightly ironic, considering who will likely own her paintings. But I have no reason to suspect any ill-will on Klein’s part. If anything, it further connects her work to its subject matter and history, and in a not so comfortable way. This is important work. It finds deep intuitive connections between its medium, its world, and its history, and gives it a critical expression whose affective force and visual beauty speak, uneasily, for itself.

Kristen Ihns is completing her PhD at the University of Chicago, where she studies contemporary poetry and experimental film, and works as an editor at FENCE and Chicago Review. She also writes poems and makes films, sometimes as part of the video collective dunt project.

Rae Klein

“LOW VOICE OUT LOUD”

June 25th – August 13, 2022

Nicodim Gallery

1700 S Santa Fe Avenue, #160

Los Angeles,CA 90021

www.nicodimgallery.com