The meteoric rise of Artificial Intelligence, or AI, in 2023 has commanded our attention. From its popularity on platforms like ChatGPT—capable of generating and editing text with a few simple commands—to headlines of Hollywood on strike to renegotiate contracts based on AI’s newfound capabilities, to even President Biden’s recent executive order ensuring the “safe, secure, and trustworthy development and use of Artificial Intelligence,” it’s evident that AI is infiltrating more of our daily lives. And the art world is no exception. Amidst this sea of confusing terminology, news, and hyperbole, artists have raised legitimate concerns about copyright issues, especially as AI learns from freely-scraped web images and produces “artworks” that mimic their artistic style. Despite this apparent threat, AI also presents opportunities to artists who seek to explore its capabilities as a tool and teachable assistant—and for Los Angeles-based Argentine artist Analia Saban, AI presented the next logical step in her artistic practice.

In Saban’s latest solo exhibition, Synthetic Self, which took place at both Sprüth Magers and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery in Los Angeles, she presented an insightful investigation blending both digital abilities and natural materials. An ambitious exhibition that concluded last month, it featured sixty-three new works that spanned across sculpture, painting, tapestry, and clever tech-centric mixed media. Deeply philosophical, the show eloquently questioned and reframed the role of an artist in an ever-expanding technological and AI world.

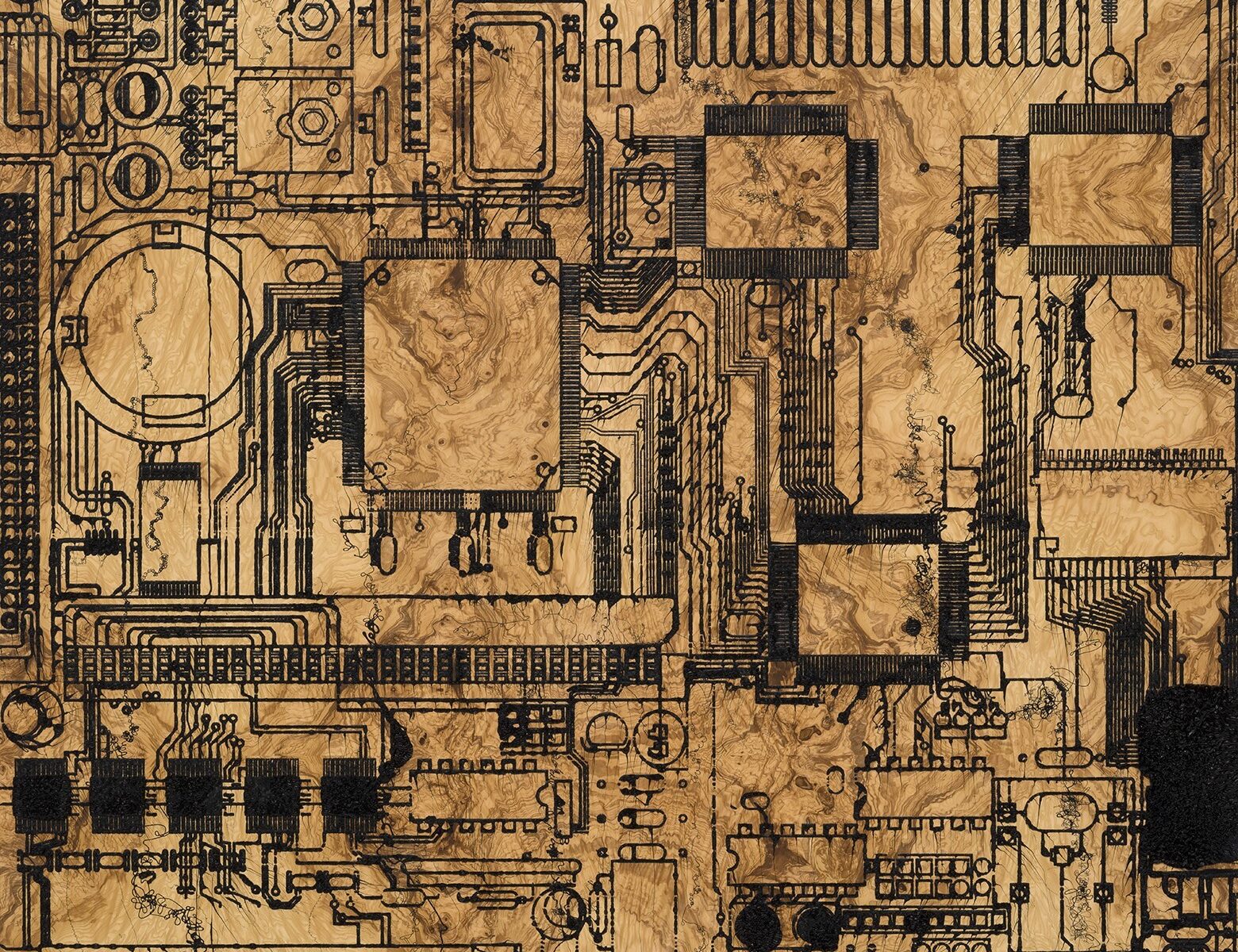

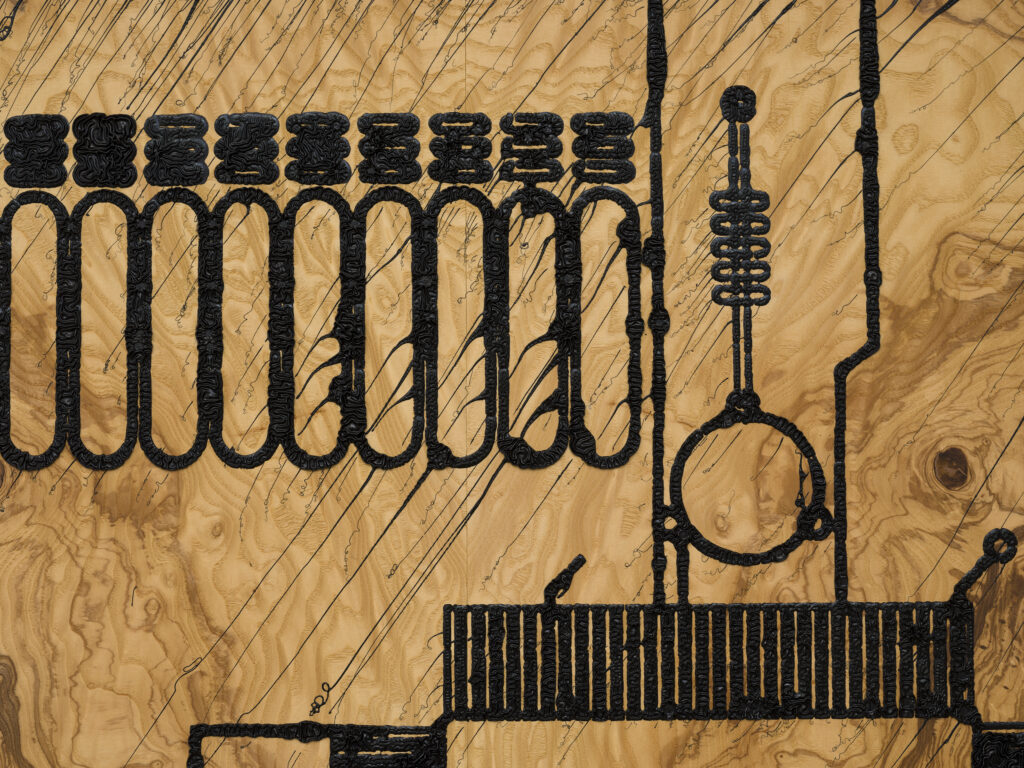

When describing her show in an Instagram reel, Saban expressed, “It’s a show about: What does it mean to be an artist these days? What’s the creative act and what are our gestures that really count?” After traversing through both galleries, viewers witnessed how this very thought process unfolded as the complete essence of the term “artist” manifested in an exhaustive selection of media, methods, and materials including linen, copper, stone, wax, graphite, wood, oil and computer parts. Throughout both exhibition spaces, viewers were encouraged to discern and question which elements were “synthetic,” by the artist’s hand, or something entirely novel. The artworks presented in the show addressed Saban’s role as a creative force and showcased her commitment to a dual approach to this new technology, utilizing it as both a tool to create elements of her works and, at times, treating AI like an apprentice by teaching it in-depth explanations of how to create various works of art.

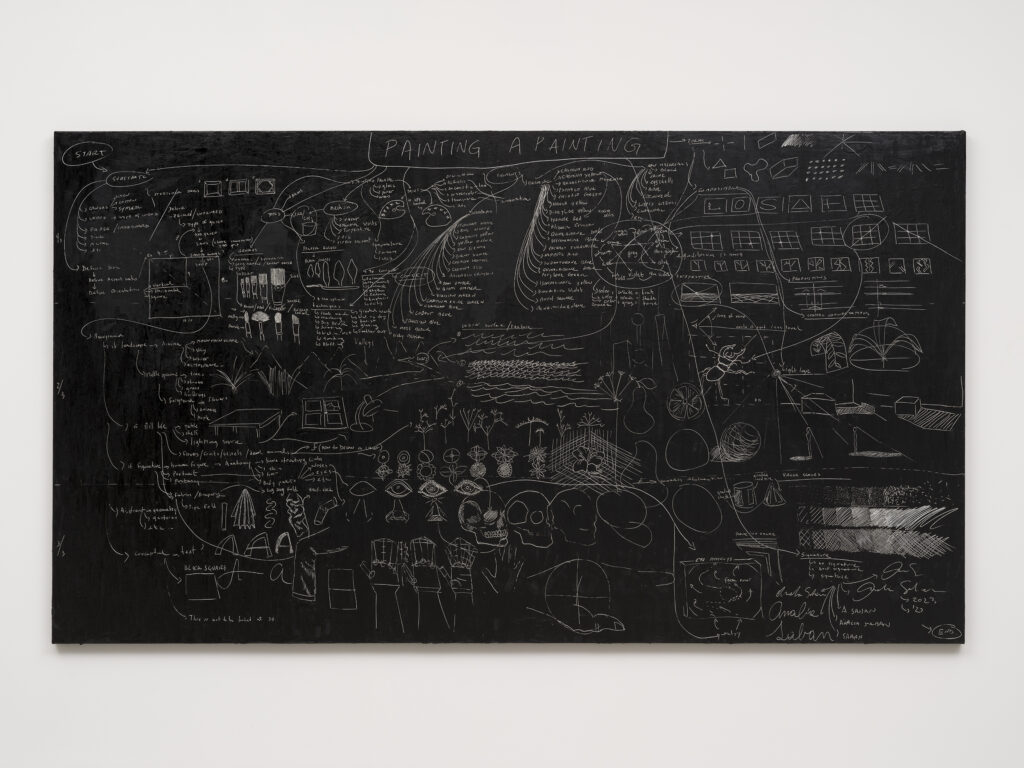

One such work was Flow Chart (Painting a Painting) (2023). In this work we encounter a sprawling blackboard-inspired canvas filled from edge to edge with writings, directional arrows, and sketches in white. As the title suggests, the artist has meticulously designed a comprehensive flowchart detailing the steps a potential artist might undertake to begin and complete a painting. Careful consideration is given to elaborate on each element such as comprehensive lists of pigments, illustrations of various brush shapes, and detailed diagrams on how to draw a hand, eye, and skull. One particularly intriguing step involved a signature, where the artist offered seven variations of her name before culminating in a circled “END.” Curiously, this exhibition marks the first time Saban has incorporated drawing into her work. This emphasis on mark-making shows Saban considering her physical role as an artist where she ultimately created an analog artwork to train a future digital AI in the art form of painting.

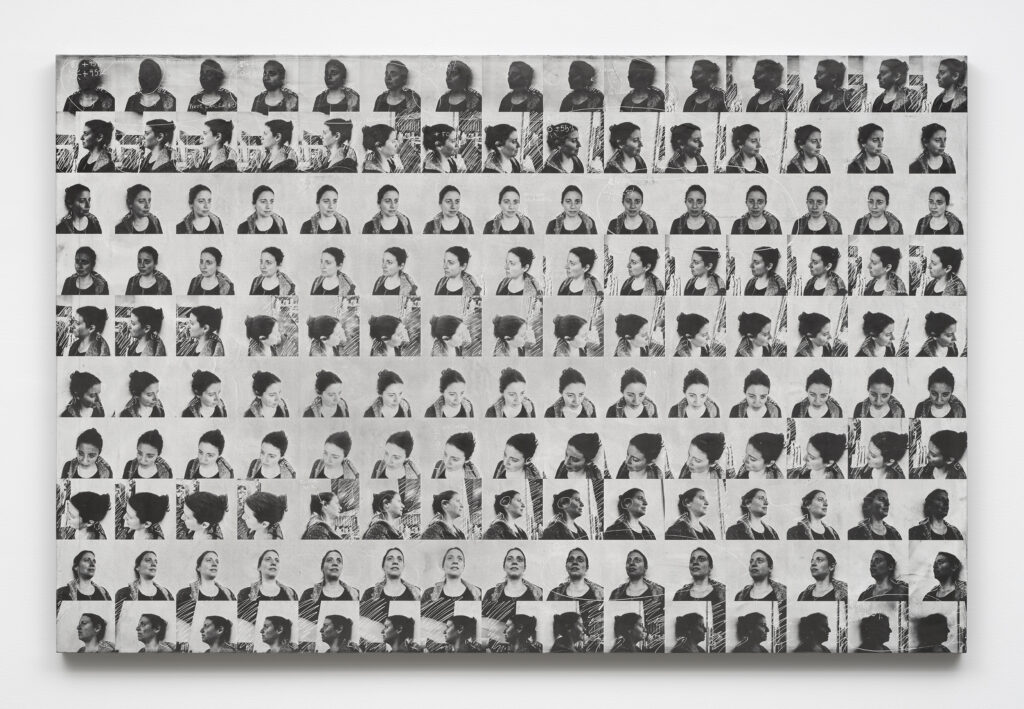

Another standout painting was Face Mapping (2023), which included 150 photos of the artist’s face at different angles. What set it apart was the deliberate decision not to digitally alter the errors and inconsistencies present in each photo before printing; instead, they are left intact. Many images on the grid bear notes to “remove hair” or feature scribbled-out backgrounds and again emphasize the artist’s hand. This work also served as a study or training tool to craft a “deep fake” of the artist’s likeness, Prompt Drawing: Deep Fake (2023), which feels reminiscent of a 1980’s school portrait with three floating heads of different sizes all gazing to the left. Together, both works question and challenge how we think about, categorize, and consider art. Can this still be considered a self-portrait with so much input from AI? Is a self-portrait only about capturing the likeness? Or can it be acceptable for Saban to simply ask the image generator to craft all her self-portraits? The number of questions raised by these works is dizzying.

A great analogy of thinking about AI’s role in Saban’s work is within the constructs of a traditional artist’s workshop. During the Renaissance, inexperienced youths—almost always young boys—would take an apprenticeship under a master artist to learn the trade of painting, metalwork, or sculpting. They would learn the basics, such as preparing the support structures, or grinding and mixing pigments, and would eventually participate in the creation of a finished work. Customarily, the master would sketch or design how the work would look, and then the workshop full of other artists would complete the masterpiece under his watchful eye. One famous example would be Andrea del Verrocchio’s The Baptism of Christ (c.1475), where his young pupil, Leonardo da Vinci, beautifully painted and rendered one of the kneeling angels.

In the context of Saban’s exhibition, the title implies that she views her artificial “apprentice” not as a separate entity, but as a “synthetic” extension of her own artistic practice. Consider it more like training a craftsman for her workshop rather than training the next Leonardo. However, the fact that she does train AI like an assistant or apprentice prompts even more questions: Will AI ever be accepted as an artist in its own right? Can art only be made by humans? Should art only be made by humans? Do any of these questions even have answers yet?

At the end of her interview clip, Saban prophetically asks: “What is the point about technology right now?” I believe she alluded to an answer in her show: Like every other tool we’ve created, it should be used while also thoughtfully considering the impact it will have on ourselves, society, and the environment.

Synthetic Self was a very timely exhibition that grappled with both the anxiety and potential of AI. It fostered critical questions about the evolution of art media and tools as well as the complication of technology’s role in creating art and how the artist can and should fit into this equation.

Analia Saban

Synthetic Self

September 14 – Oct 28, 2023

Tanya Bonakdar Gallery

1010 N Highland Ave

Los Angeles, CA 90038

Sprüth Magers

65900 Wilshire Blvd

Los Angeles, CA 90036

Installation view by Jeff McLane.