While the majority of Americans, 72% according to a 2021 poll by Yale University, believe global warming is happening, only 47% seem to believe that it would harm them personally. This alarming second statistic seems to prove the national disconnect as to why most individuals don’t seem to “feel” the same urgency as those who live in areas prone to extreme drought and fires like Los Angeles. How do we bring them into the fold? Apparently, it is not through statistics, news, or testimonials by expert scientists, which have been abundantly available, but likely will be through bold, thought-provoking images made by artists who conjure deeper emotional connections, as was the case with 19th century artistic movements such as the Hudson River School. Perhaps this is why the recent group show Mapping The Sublime: Reframing Landscape in the 21st Century, felt needed, as if it were answering a call to arms.

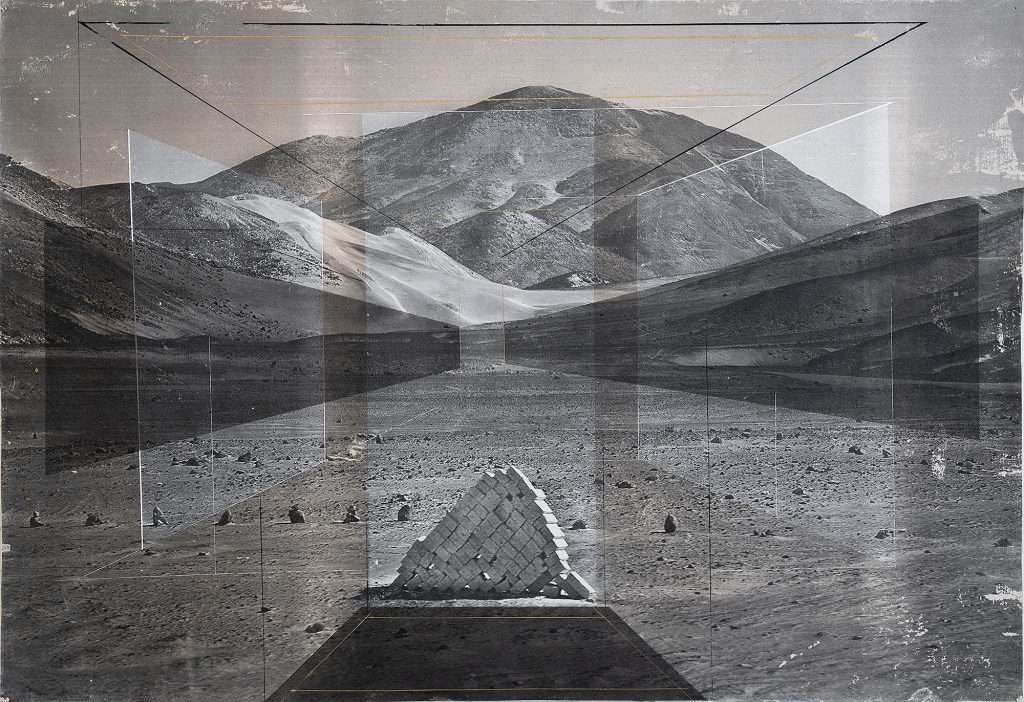

Organized by artists Lawrence Gipe and Beth Davila Waldman, the ambitious exhibition included multiple artworks by each of the twenty artists working in a variety of media including: video, photography, collage, installation, and painting. Gipe and Waldman chose these artists —Luciana Abait, Kim Abeles, Fatemeh Burnes, Linda Connor, Rodney Ewing, Guillermo Galindo, Dimitr Kozyrev, Ann Le, Constance Mallinson, Ryan McIntosh, Liz Miller Kovacs, Deborah Oropallo, Andy Rappaport, Kit Radford, Aili Schmeltz, Alex Turner, Rodrigo Valenzuela, and Amir Zaki—as their practices incorporated landscape and the sublime to reflect upon critical issues of climate change and the Anthropocene.

Meandering through the multi-roomed exhibition, one feels a sense of the scope and complexity of the obstacles we face as a civilization. We are confronted with mass extinction, melting glaciers, toxic waste, and vast regions negatively transformed by our human presence, among other issues. While these are all known and acknowledged problems, here they are reinterpreted in the context of the sublime, and then presented as physical objects for contemplation.

In Constance Mallinson’s installation, It’s Amazon, Stupid (2022), viewers are lured in by a glass vitrine of oil paintings. The paintings are made on neatly cut pieces of found Styrofoam, and depict pleasing images of “exotic” flora or fauna from disappearing landscapes around the world. Seeing such highly detailed and colorful paintings rendered on trash, one can’t help but think of how we often treat nature as disposable and expendable. One also can’t avoid the cruel sense of irony by using Styrofoam, as this human-made product will certainly outlast the living inhabitants of these natural habitats.

Another fascinating grouping was a series of photographic works by Alex Turner that explores both the sociopolitical and environmental issues at the border between the U.S. and Mexico. Turner captures the hidden movements of animals and humans traversing the shared landmass by marrying photography and remote sensing imagery. In 29 Humans (Smugglers) and 12 Horses, 1-Week Interval, Patagonia Mountains, AZ, (2019), we see a jumble of figures with heavy packs and intermittently visible horse legs, all lined-up on the same path as documented over the one-week period. By depicting them as a ghostly mass, the artist transforms their presence into a fixture of these desert mountains. Yet the use of “spy” cameras to capture these previously unknown paths feels dangerous in the wrong hands, especially in today’s political climate.

Mallinson, who also contributed a must-read essay to this exhibition, stated, “There are no neutral landscapes.” In this show each artist takes full advantage of their license to delve deeper into the consequences and cautionary tales of our destructive behavior toward the environment and our “ungovernable technologies.” Yet, it’s their use of the sublime in landscape that tethers the viewer to a more personal and spiritual experience.

The exhibition’s theme also had strong art historical parallels to the father of Hudson River School painting and 19th century environmentalist, Thomas Cole. He too used the sublime in his famous landscape paintings to instill both a feeling of awe and power in nature, but also to help people comprehend what they were losing to industry and greed—a trend that continues today. In his 1835 Essay on American Scenery, Cole wrote:

I cannot but express my sorrow that the beauty of such landscapes are quickly passing away—the ravages of the axe are daily increasing—the most noble scenes are made desolate, and oftentimes with a wantonness and barbarism scarcely credible in a civilized nation. The wayside is becoming shadeless, and another generation will behold spots, now rife with beauty, desecrated by what is called improvement. […] Nature has spread for us a rich and delightful banquet—shall we turn from it? We are still in Eden; the wall that shuts us out of the garden is our own ignorance and folly.

While it is not the artist’s responsibility to change the hearts and minds of Americans about climate change or encourage them to take action, this exhibition demonstrated that they can certainly provide the “map” for navigating our 21st century landscape. Here’s hoping that our “ignorance and folly” won’t keep us from asking for directions.