The Balloon Museum’s website touts it as the “Best Event in the World” with “7 million visitors” worldwide, across 5 countries — its latest exhibition Let’s Fly, in Los Angeles, is open through March 16.

My partner suggested it as a date night. I rolled my eyes. Another Instagram-photo-op “experience.” Woohoo.

But something also tickled me. At $50 a ticket with timed entry, this capital-E Experience seemed, incredibly, to be something people were buying into. Art museum attendance has been declining since the year 2000, according to the National Endowment for the Arts’ Survey of Public Participation in the Arts. What was it here, with no household-name artists, that was attracting families and date-night couples well beyond the usual art museum suspects? I wanted to find out.

Let’s Fly in Los Angeles —one of the four curated exhibitions that travel worldwide—is located in the same huge warehouse downtown where I first visited Luna Luna, an event that re-created a 1987 art amusement park from Hamburg, Germany, featuring work by Basquiat and Keith Herring. The Balloon Museum, in contrast, has no marquee artists. And that, it turns out, becomes kind of the point. The marquee artist here is you.

People come to this place dressed up for a photoshoot. Our “press tickets,” when we get them, are labeled “creator tickets” — we’re working in a different realm of conversation about aesthetics, one less bound by traditional art-world gatekeepers and instead circumscribed by viral reach. And really, the social media creators are the ones doing this place right — using it as a canvas for their own art. The photos you can take are incredible. Without them, there’d be no point.

On arrival, it felt like we were entering an amusement park, with stroller check and colored lines for timed entry. My partner and I caught the final showing at 6 p.m. on a weeknight, so most of the other attendees were couples on dates, though we watched tired families with young kids file out as we came in.

Entry to the warehouse took us through brightly colored, inflatable archways. Inside, we were confronted with—ourselves. At the entrance to the first exhibit was a full-body mirror, surrounded by projections of shifting colors. Going around the mirror, we entered a hallway walled with more mirrors, with a mirror floor. We watched ourselves enter. We took selfies.

In the next space, a row of hanging, massive black inner tubes moved up and down like sections of a hollow worm to expose and then hide a bright light. I was reminded of James Turrell’s experiments with light and movement, the defamiliarization of our eyes that allows us to perceive color and shape in new ways. Like Turrell’s work, each exhibition created an encompassing environment shaped by light—but where Turrell is minimalist, focusing our quiet attention on the mysteries of color, Let’s Fly explodes with it and adds music. It’s Turrell, but it’s also a rave.

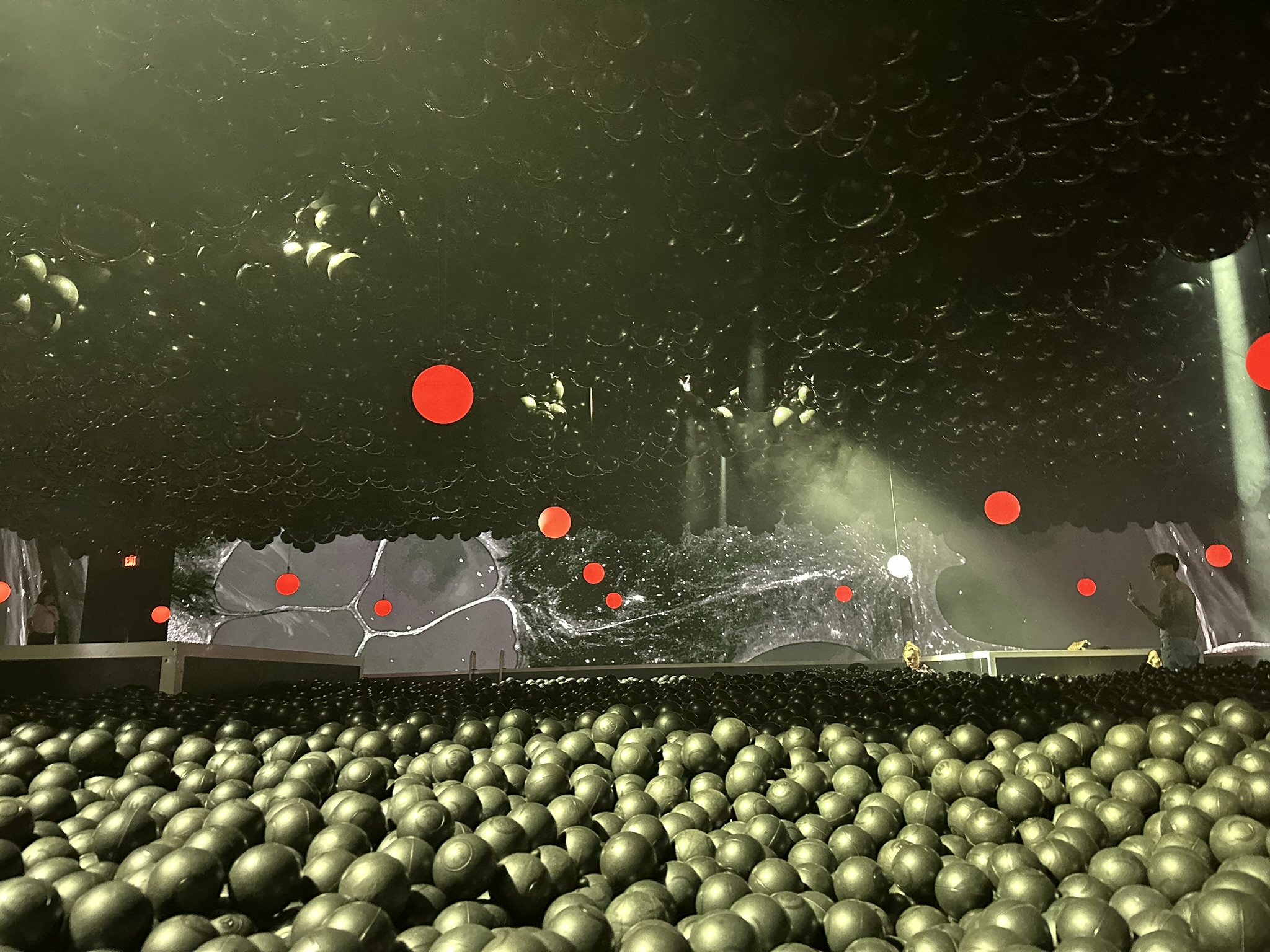

Past the moving ‘donuts,’ we entered an inflatable maze—fleeting impressions of a McDonald’s PlayPlace, structures that invite crawling, changing levels, getting, literally, into the art. And where should this lead but a literal ball pit—all black, because, art. The ceiling is a bulbous mass of black balloons, with video of exploding color on all sides.

The pit invited us to dive in, and we obliged, joining the museumgoers already lounging neck-deep in plastic balls or throwing them at each other. We sank and saved each other. The balls became a relational element, not something to look at or even sit on, but the medium we were literally wading through—the space between us literalized in black plastic.

Much as the wall text for this piece (Hyperstellar) vaunts the idea that it’s about our place in the universe and relationship to the cosmos, what’s missing is a strong point of view. Are we small? Interconnected? Atomic? We are left bathed in experience, perhaps even changed, but thinking no new thoughts. The pleasure, here, is the point.

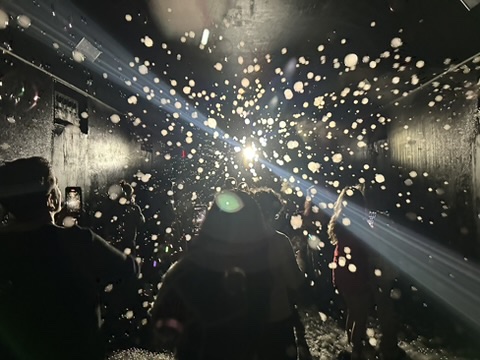

“Bubbles, yes!” someone exclaims as we enter the next room. And, indeed, bubbles. There’s a joy in the familiar, as a piercing light through the suds casts an ethereal glow. Everyone instantly has their phones out. But then, as the bubbles ricochet into our faces over and over, it’s too much. No one stays in that room for long.

We stumble out and into the room of the Ginjos creatures, giant inflatable ‘eggs’ with eyes who babble nonsense dialogue. My partner runs through them, knocking them this way and that. Someone starts boxing the critters, and soon everyone is laughing and throwing punches, knocking the egg-people into each other. Again it’s relational, and here it hits me—it’s not about the relationship of the people with the art, like a traditional gallery. Instead, the art becomes a vehicle for people to explore their relationship with each other.

The point of these Instagram-friendly museums is not what the artist is expressing through the art, but rather how the art makes you express yourself. The art isn’t there as an artifact, but as a provocateur.

“With art you’re always told not to touch,” my partner exclaims happily in the swinging ball room, pushing a cushiony ball on a rope hanging from the ceiling as hard as he can. There’s a rebellion in the act that the museum invites, but it goes deeper than touching the art. As the hanging balls swing, the interplay of light and color in the room is altered—the spectator is no longer merely observing the aesthetics, but causing them to shift through their actions.

When Dada artist Marcel DuChamp said the “audience completes the artwork” — is that this?

No, I think. Because that was about interpretation: a picture of a pipe, the words “this is not a pipe,” and the meditation on being versus representation. Let’s Fly isn’t trying to present something to be interpreted, but to be inhabited. We create the picture, and the caption—they provide only the hashtag. The objects here are not presented as sites of contemplation, but sites of action.

In the inflatable giant finger room, columns rise and fall while you lay on fuzzy inflatable couches (built for two, ooh la la). The next room is full of bean bags under a light-up butterfly. I think, I don’t know that I’ve ever been to a museum that encourages cuddling the way this one does!

The butterfly ripples with color, to soothing music. If you sit on the swing bench (big enough for five) and rock, you can make its wings flap.

We’re almost through. Along with the other guests, we pushed a giant ball covered in charcoal spikes around a white room, leaving abstract marks on the walls and ceiling—a deconstruction of process art. It strikes me that we’d begin to interact with the strangers alongside us on a different level than most museums provide. We were engaging on the level of play.

We’ve seen each other’s responses to a dozen rooms by now—we know each other more viscerally than we would after a conversation. We know one another’s reactions to bubbles and punching bags and ball pits. There is a magic to re-inhabiting childhood. And as cynical as I start, by the time I’m through, I do feel a sense of childlike wonder.

Of course, childhood never lasts. Cue the hovering parent with the camcorder. We have to document, to remember ourselves at our most pure before the everyday seeps back in.

Obligingly, the journey through The Balloon Museum ends in a corridor walled by photo ops. This is pure documentation—“one last selfie!” it seems to say—for the completionists, so you don’t feel like you’ve missed anything. There’s no attempt at immersion or pretension at high art. You can be under a cloud (of balloons), or with a giant teddy bear (of balloons), or with angel wings (of balloons—but deflated ones, admittedly a clever twist).

The selfie corridor ends in a museum shop, of course, with stuffed animal Ginjo creatures and t-shirts. An experience needs documentation to be real. A memory requires an artifact.

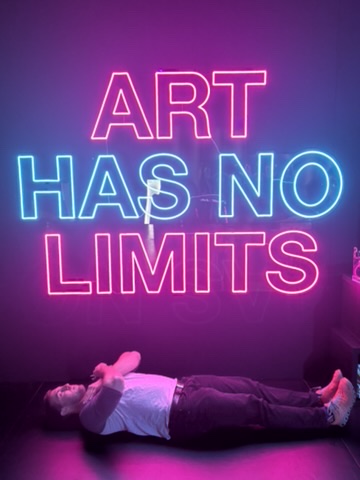

Before the exit is a statement, the tag-line of the exhibition, in gorgeous neon:

“Art has no limits.”

And then—there’s more stuff to buy. Candy!

That’s The Balloon Museum.

The word “museum” comes from the Greek mouseion, meaning “seat of the muses.” There are many ways to have a muse, to hear it speak to you. Most museums are contemplative—this one is active. I wonder if our artists and institutions might not take a cue from this space, to allow people into the artwork—truly in—if the goal is to remove the distance between art and an increasingly alienated American public. If art is to be successful in this age, it seems, it’s not enough to be a site of contemplation, it has to become a site of reconnection.

Or, more ominously, in an age when everyone must perform themselves incessantly into existence, for art to exist, it must weave itself into this performance. Every artwork must make itself a stage. And where’s the role of artist as truth teller, if the model is artist as decorator?

Balloons return us to play through nostalgia, evoking childhood and celebration. But The Balloon Museum isn’t here to have you reflect on these things—it’s here to have you recreate them. The thing is, a photo is always a step removed from reality, and after visiting The Balloon Museum, I better understand that uncanny feeling I get with Instagram museums. It’s the distance between reenactment and real experience.

The Balloon Museum was a lot of fun—or, at least, a lot of the appearance of fun.

But don’t we always remember things more fondly in the photos?