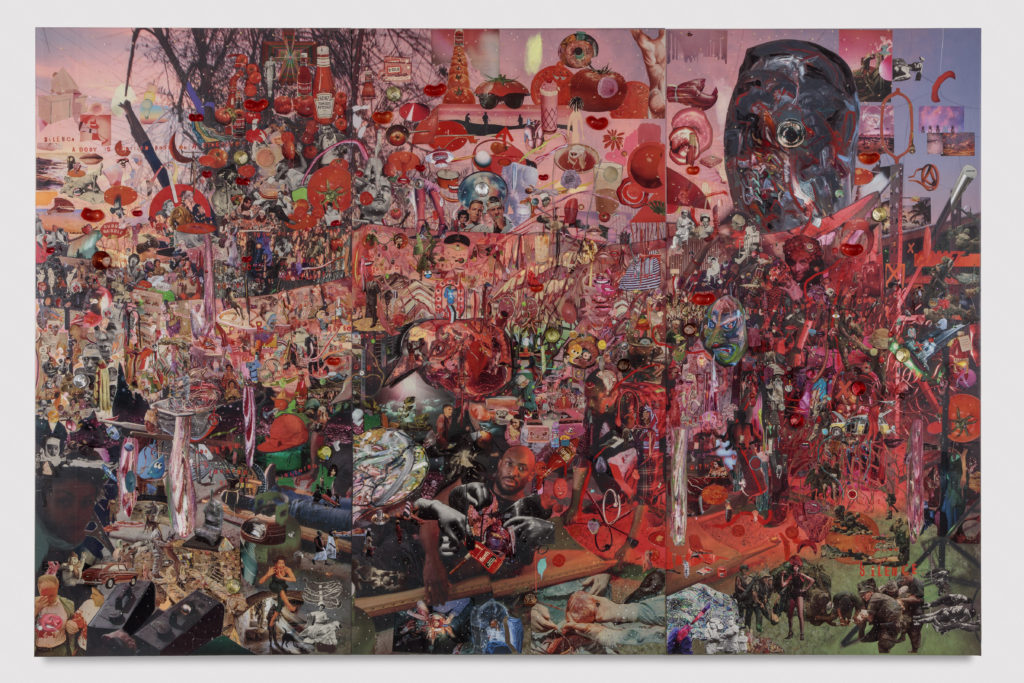

Understanding the chaos and grandeur of Elliott Hundley’s collage works means understanding the fundamental unit of their construction: the intimate and almost sentimental act of sifting through old objects and images, delicately cutting them out from their original form, and then placing them on pins as if they were entomological specimens. Hundley does this hundreds if not thousands of times, though—often without attaching any images or ephemera to the pins—transforming the act into something obsessive and seemingly pathological.

It’s easy to see how Hundley’s collage works earned him success. They stage a collision of different eras through the old and familiar tradition of collage and the post-internet age of information abundance, two visual languages that certainly have a household presence. And they stage that collision such that their commentary on contemporary life can be understood through the experience of viewing them, instead of through some theoretical exercise. Hundley is at his best with works like The Plague (2016), where he’s cultivated the intimacy of a Joseph Cornell boxed assemblage, but also the mood and grotesque sprawl of a Hieronymus Bosch landscape.

Echo, a twenty-year survey of Hundley’s work at Regen Projects, features some of these collage works, alongside an array of others, including freestanding and hanging sculptures, assemblages, paintings, photographs, ceramics, and works on paper. There is even a hallway displaying what seem to be objects of personal importance to Hundley, interspersed with some of his smaller works. Echo is installed and presented as an immersive experience into the artist’s practice, and touches on his usual themes of excess and abundance, but this show feels more like a product of its time and less of a commentary on it.

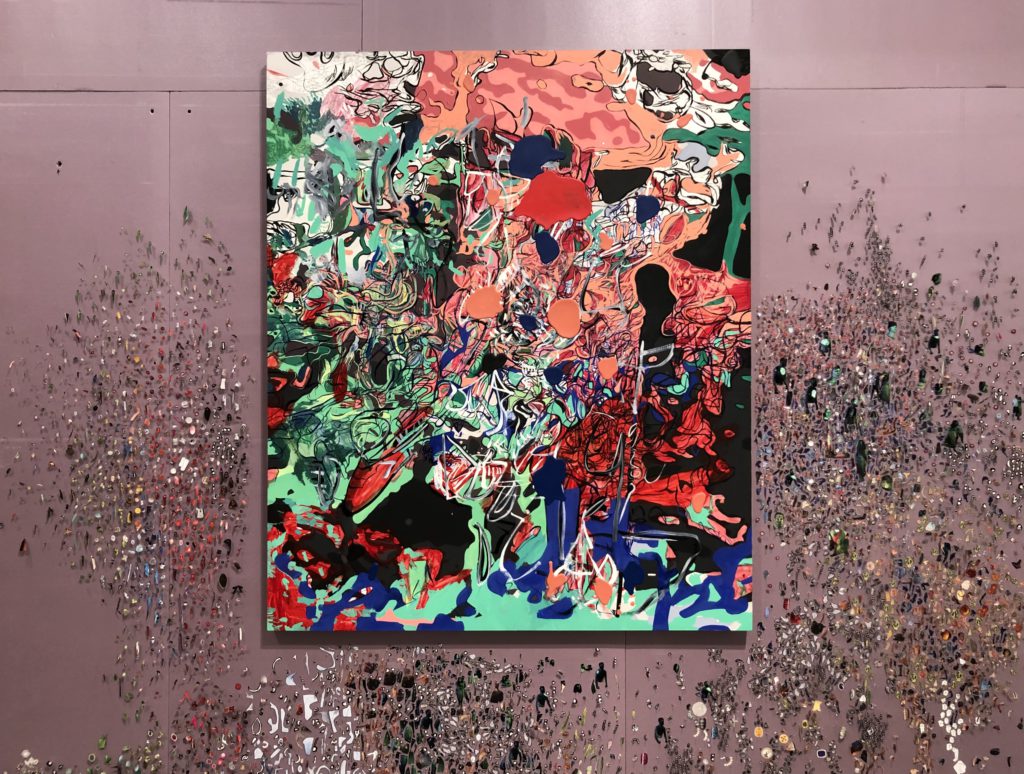

Echo is installed much like Hundley’s collage works are assembled. Swarms of pins and miniature images hover around individual works, which, according to the press release, was inspired by Hundley’s studio. This salon-style, everything-everywhere approach would seem to make sense, as it’s consistent with the themes of his work and provides a way to link the different media of his oeuvre, but it overreaches. There is so much going on—so many pins, so many choices, so many images intricately cut out—that it is implausible, if not impossible, that Hundley eked out this exhibition himself. Just looking at all of Echo can be measured in man-hours.

Fine artists use assistants all of the time, and for the most part it’s uncontroversial and no one even notices or cares. Filmmakers use hundreds to thousands of people, and this is seen as perfectly normal if not optimal. But there is a problem with it here. Hundley’s collage work is inherently intimate and personal, if not presented and promoted as such. When the use of assistants becomes so conspicuous, as it has with Echo, it changes the nature of the work. After all, part of what makes Hundley’s individual collage works great is because they seem created by one person. Breaching that semblance, Echo becomes less about the obsessive, intimate act of the artist—and the extraordinary effort and care of one man—and more about the manufacturing of it.

Echo’s conflict between feeling intimate or manufactured seems befitting in a culture that increasingly struggles with its own competing desires for authenticity and illusion. In a time when everyone has a camera, editing software, and a platform, there is not only a trend toward constantly staging and curating one’s life, but also a revulsion to it. As for Echo, maybe it shouldn’t matter how the art is made, and that manufacturing something intimate is perfectly acceptable. But if that’s the case, we need to ask ourselves some probing questions about our tolerance for illusion, if not our desire for it.

It’s also questionable what Echo really achieves by its installation. It does blur the line between the art and the process of making it, but it creates perceptual issues with its more-is-better ethos. Unlike Hundley’s individual collage works—which do corral overwhelming amounts of information into something more—Echo strains to tie together every collage, sculpture, painting, pin, image, brushstroke and scrap of at least three rooms of the exhibition.

Echo wants the viewer to conclude that its whole is greater than the sum of its parts, but the installation lacks the synergy or dynamic interaction of its parts that usually leads to that effect. Instead, it achieves something close to the opposite. Echo’s installation spreads the viewer’s attention so thin that each individual work seems to have a more important role as a mere part of the whole; and because of that, less is expected from each work. At worst, the more an individual work blends into the rest of the installation, the more it feels like decoration. What this adds up to, it seems, is Echo asking only one thing from the viewer: to marvel at the immensity of its production.

There is an appeal to the spectacle of the installation, but I can’t help but think that this is because contemporary viewers (myself included) are conditioned into having their attention spread thin, and that low bandwidth shapes what we’re drawn to. Maybe tapping into this is ingenious of Hundley. Maybe it’s pandering. Maybe it’s unintentional. But it feels like something I would expect more from a social media company than from an artist.

Like Echo’s installation, Hundley’s paintings seem heavily influenced by his propensity for hyper-collage. But it doesn’t make for good paintings. For one, Hundley is prone to cramming too much information into his paintings. There are so many styles, marks, layers, and clashing colors—all densely packed into one canvas—that it is hard to take anything from these paintings other than “the chaos is the point.”

Maybe worse, I think Hundley’s predilection for collage makes him quote other painters a little too much—almost as if he’s collecting marks and styles like one would endearingly collect objects or images for a collage. Works like face and form (2013) and Untitled (2013), for example, are suspiciously similar to the work of Albert Oehlen. Of course, artists are always drawing from, and building on top of, the work of other artists, but in the incremental difference between Hundley’s paintings and his precedents, it’s hard to discern what Hundley’s contribution to painting is, if anything. And at a gallery as eminent as Regen Projects, the inclusion of these paintings begs the question.

Hundley deserves the acclaim of his collage works, but what made those works great does not necessarily scale up or translate well to other media—and neither of those things make Hundley the artistic polymath he is sometimes thought to be.

I still found Echo to be a noteworthy exhibition, though. From what I can tell from the responses of other writers and artists, Echo seems to be quite polarizing. It’s hard to sense decades-long shifts in cultural and aesthetic sensibilities, but—to me, at least—that polarizing response is what slow-moving change feels like in the moment. So, in some way, Echo did leave me feeling immersed, just not in the show itself.

Elliott Hundley

Echo

January 14 – February 19, 2023

Regen Projects

6750 Santa Monica Boulevard

Los Angeles, California 90038

www.regenprojects.com