“All meaning accrues in duration.”

-Ken Burns*

Memory, nostalgia, duration, rhythm, repetition — time. A Journey That Wasn’t purports to show works of contemporary art that “[consider] complex representations of time.” It’s a pretty open brief, but one that allows for an unexpected and playful grouping of works from in and around the vast Broad collection. I’ve been a couple of times now, including once with a group of my film students. It’s an exhibition deserving of repeat visits.

A series of trompe l’oeil paintings by Ed Ruscha are the first to greet the viewer. The diptych Azteca/Azteca in Decline (2007) sets up one of the show’s primary themes — decay. Three smaller paintings, Atlas, Index, and Bible (all 2002) suggest a guidebook of some kind, but give only the exquisitely painted surface of such on raw linen.

Seated Woman (1999-2000), a life-like, but not life-size, old woman by Ron Mueck sits contemplatively next to the fireplace of Toba Kheedori’s wall-sized Untitled (Black Fireplace) (2006). The woman is small against the vast white wall, and there is a tension between her size and her level of detail, a tension reflected in the foreboding black surrounding the warm fireplace.

The docent was discussing Mueck’s sculpture with my students, and it’s use of scale as a perceptual point of friction. She went on to expound upon another phenomenon of the work that only becomes apparent in the photographing of it. When photographing the sculpture in profile, another person can stand just beyond the woman, and in the resulting photograph (due to the camera’s flattening of depth) the woman appears to be life-size. However, in shooting the same subject, this time with the person on the same plane as the sculpture, her true small scale is revealed.

To a group of film students, this was an interesting aside, but not a revelation. We’re all familiar with the technique of forced perspective; the cinema has been making small things appear larger than they are since the beginning. What was striking about this demonstration is that it called attention to the realtionship of photographic (or at least photorealistic) representation to the work in the exhibition. Perhaps it is an assumption taken for granted that in representing time in the ways the exhibition does, concrete objects are necessary. We can consider the effects of time on things more easily than we can as an abstract phenomenon. Aging and decay are processes that act on people and things. And much of the subjects represented are indeed humans, which are, to use Heidegger’s term, beings-in-time. That is, to be human is to experience time. We have memories of things past, an awareness of the aging and death that awaits us, and in between a slippery conception of the present, of time to be spent, used, wasted, etc. Photography and cinematography both have direct, formal relationships to time, and so it is fitting that much of the work falls into these categories.

Andreas Gursky’s F1 Boxenstopp series is on display. The large-sized frozen moments of Formula One pit crews have all the drama and visual density of a high Renaissance tableau, while strong horizontal lines and symmetry provide visual stability in the works. Elsewhere, the black and white Water Towers (1972) series from his teachers, Berne and Hilla Becher, share a room with Gregory Crewdson’s (also black and white) photographs of Rome’s derelict Cinecittà Studios from 2009. Seeing the site of cinematic production in decay through the lens of an artist who uses the tools of cinema to evoke scenes of suburban decay. It’s an interesting inversion of his conventional oeuvre (I’m thinking here of his Hover series, which is also black and white, and his Twilight and Dream House series), like flipping the card over and seeing the other side of an artist’s work, or like some perverse making-of featurette.

The eponymous Pierre Huyghe film, A Journey That Wasn’t (2006) operates with its own internal inversion. The film is part documentary, part operatic performance of light and music, intercutting Huyghe’s journey to Antarctica in search of an albino penguin with a staged recreation of that journey on an ice rink in Central Park. Slow, undulating icescapes in washed out blue contrast with pulsating tungsten stage lighting in Central Park. The cold, misty Antarctic is replaced in its recreation with fog machines pumping out atmosphere. In Antarctica, the camera does find the elusive penguin, whereas in Central Park an animatronic version of same is presented exclusively in silhouette. Viewing the actual event with the dramatized memory of it juxtaposed in real time suggests that perhaps reality, or the human experience of it, resides in the mediating of an experience – a necessary precondition for the sharing of an experience. The story behind the piece is that during the course of this journey, Huyghe was able to encounter lands previously inaccessible due to the ravages of climate change. In this way, the journey that was planned is perhaps the titular “journey that wasn’t,” and the journey as staged in Central Park is also clearly not the journey that happened.

In cinema, the camera is always encountering its subject – whether that subject is sought out by the operator documentary style, or whether it is placed deliberately in the lens’ field of view. There is a phenomenological cohesion between the shots of the actual journey to the Antarctic and the staged recreation in Central Park (simply put, they’re both sets of filmed images, and the camera never questions the veracity of what it captures). In a work that questions where the reality of the journey lies (what was the journey?), its filmic presentation provides some clues. The heat, the fog, the smoke in the Central Park recreation say something about climate change that the mute Antarctic landscape cannot. However, the documentary evidence of the voyage is as important to the meaning of the work as is the emotionally inflected restating, as the film is a response to a very real encounter with the effects of climate change.

Reality necessitates fiction in its expression, documentation requires imagination in (re)presentation. This juxtaposition between documented reality and recreated memory also serves as brackets for the rest of the exhibition.

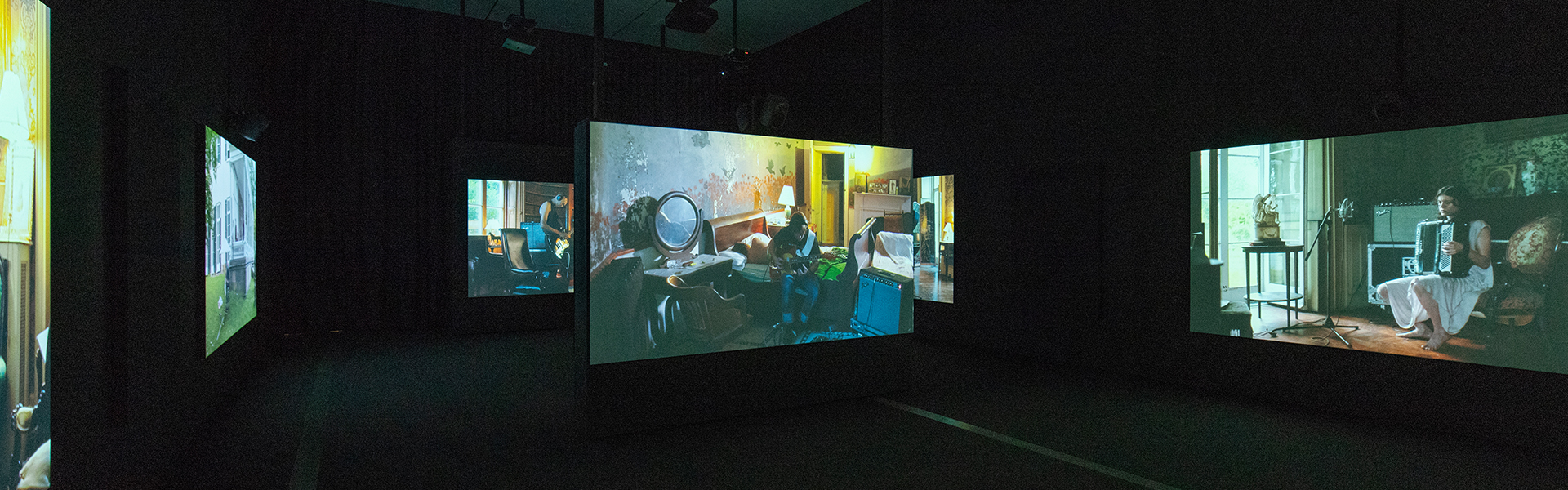

If A Journey That Wasn’t offers a juxtaposition between the filmed reality and the cinematic presentation, then Ragnar Kjartansson’s The Visitors (2012) creates a unified transformation of one space into another. Specifically, a farm house in disrepair is transformed into the installation comprising nine high-definition projections, each with its own audio feed. The tableau include musicians with their instruments in various rooms of the Rokeby farm house in upstate New York. The musicians all wear headphones, and are all contained within the bounds of a frame (though one or two may break those edges at various times), thus isolating themselves from each other visually, but united aurally. The ensemble all play the same song, drifting in and out of unison, building and releasing intensity over the course of roughly one hour.

“There are stars exploding around you,” begins one line of the song.

The view within each frame does not move. The subjects inside do, minimally. They smoke, they fidget, they sing, they play an instrument. Space is evoked via sound, and the viewer is compelled to move amid the silence by its call. The viewer can consider each individual (though some frames are occupied by more than one subject), but never outside of the context of the rest of the set. Any “lessons” drawn from the piece feel too simplistic to articulate — it’s a complex emotional experience of the conflation of aloneness and togetherness that one must feel for herself.

“And there’s nothing, nothing you can do,” it continues.

Maybe the cinematic subject is always a tragic subject — its fate always already sealed. Once an event is captured on camera, it always unfolds in a way that is phenomenologically real, yet already predetermined. The piece is movingly sad and exuberantly joyful. The imagery is very nice, but it is the three-dimensional experience of the music, the unexpected voice rising above the others from the other side of the installation, that gives the piece its emotional impact. But, like most of the works in the exhibition, that impact unfolds slowly over time.

What you can do is visit the exhibition — it’s up until early February 2019 — and give yourself plenty of time when you do. There is much more to see than mentioned here, including Sharon Lockhart’s Pine Flat Portrait Studio Series (which also occasions a screening of the documentary film in October at REDCAT in conjunction with the exhibition), and works by Sherrie Levine, Glenn Ligon, and more — over 20 in total.

General admission to the Broad is free, advanced reservations are recommended.

www.thebroad.org